For My Children and Grandchildren

These memories were put on paper

during three or four waves of nostalgia between 1964 and 1967. The postscripts were added a little

later. When I once started writing it

seemed as if I could not stop; it simply flowed out of me with scant attention

to spelling, punctuation and sometimes order of phrasing. Consequently, C. J.

C. has been of tremendous help as editor and supporter.

My excuse is, of course, that I have

lived through enormous changes. Also I

was fortunate enough to have been brought up, during my early years, in a small

intelligent backwater of security and peace.

As the Exxon T. V. "ad"

says, "We should like you to know."

S.

E. C. 1974

S. E. C.'s Chronicle

The Early Years 1898 – 1912

Life for Theodore and me seemed

always busy, exciting, and immensely interesting though quite different for

each of us. Theodore's interest was in

man-made things - everything from clocks to chemical formulas. He had to know how things worked. He loved to take things apart and put them

together again. He taught himself

through the years the skills of plumber, electrician, carpenter, mechanic, cabinet-maker. I

admired his knowledge and his abilities but preferred the less intellectual

pursuit of just loving to be alive.

I loved the out-of-doors - earth,

sky, water, mountains, birds, flowers, animals -

especially animals. I belonged to the

natural world and loved it with passion even as a very small child. I accepted it as it was.

Yet often through the growing years

Theodore and I would team up, he to invent and I to taste the fruits of his

inventions, sometimes disastrously. I

shall never forget one early summer day about the turn of the century, when we

were at Putnamville and Mother's "Cheerful

Workers," her ladies' sewing society, were coming from Salem on the

electric cars for an afternoon party.

Theodore had announced to me that he was making a watering-cart out of a

baking-powder can. I admired greatly the

watering-cart which in dry weather

dampened the streets of our little town where

we lived in the summer. Bright yellow with red underbody and wheels, always

freshly painted, it was drawn by a pair of fat, shining chestnut horses whose

three inch high manes were cut like those in a Greek relief sculpture. They

wore harnesses decorated with gleaming brass studs and their tails were often

braided with strands of red cloth. They

moved with slow, royal dignity in the continuous round of subduing dusty

streets. I thought this a beautiful sight.

So when Theodore announced he was

making a watering-cart I had to "go and see" immediately. Its construction had started with a hole in

one end of the shiny can. I wondered

whether the hole was going to be large enough and pushed into it the forefinger

of my right hand. The fit was snug, so

snug that the jagged edges on the inside gripped my finger when I tried to pull

it out. I can clearly remember the

dawning horrid thought that I should not be able to get that can off. Also I was afraid of Theodore's wrath when he

would discover that I had been meddling with his work. Panic swept over me. I rushed to my mother, who was busily

preparing for her party, and weeping, I asked her if I should have to wear that

tin can on my finger all my life. The

ladies arrived in the midst of her patient cutting it away with her best

shears. Needless to say Theodore was

furious.

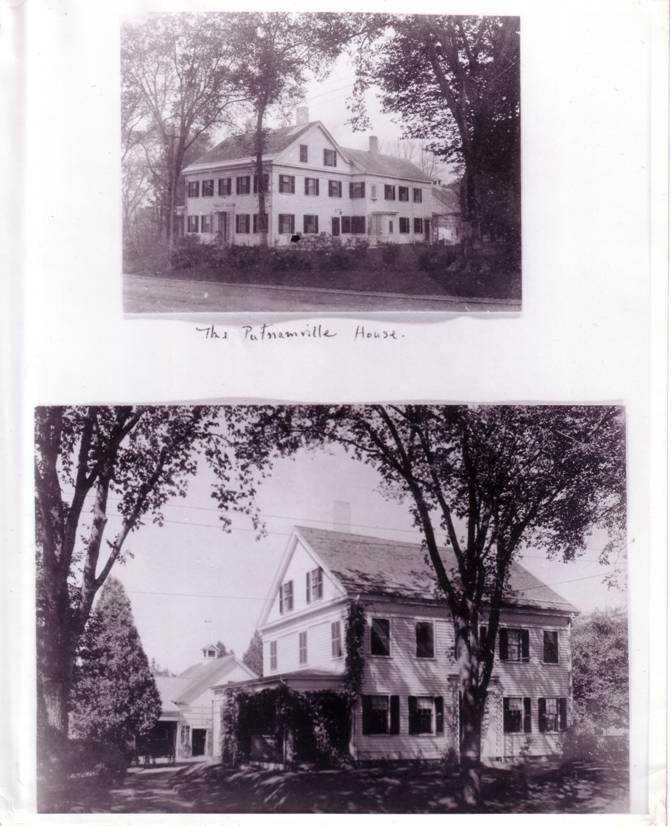

Our summer home in Putnamville was a tremendous outlet for vigorous physical

and mental energy of children. We loved

our beauti-

ful old house in Salem, but the garden

was small and quite fenced in, and, like many eighteenth century houses in New

England seaport towns, the sidewalk was directly outside our windows. There was a certain

coziness about this during the winter months when the window shades were drawn

and the shaded mantle gas-lights, turned low, made a really beautiful soft

light. We could hear the footsteps of

people passing on the brick sidewalk outside but we ourselves were quite unseen

and private in the security of warmth and snugness. As I sat on the old window seats, Stevenson's

"Lamplighter" would run through my head, even at an early age, for we

knew and loved "The Child's Garden of Verses."

But real joy came to me (I think it

mattered to me more than to the others) with the coming of early May. Usually by May tenth, my mother's birthday,

the big moving van would have arrived to transport her piano and other precious

pieces to our country house for the next five or six months' stay. The distance was only five and a half

miles. The automobile age was in its

infancy and for the first years the trip was made by horse and carriage,

electric car or steam train. Now the

suburbs have engulfed the area, and I barely recognize it. Neat streets with pleasant houses and lawns

wind about where once Mr. Lovelace's cow pastures and blueberry hillside used

to be. They have invaded the tennis

court, the horse paddock, the field of timothy grass, my mother's cutting

garden, the field where Mr. McCarthy used to grow his cabbages on land rented

to

him by my father. The house and barn and perhaps an acre of

land still survive, bereft of the softening, embracing, graceful elms. I

scarcely recognize it. The old farmhouse

behind us down the grassy lane is now a handsome suburban house, the grassy lane

a neat gravel driveway. The great cow

barn across and up the road a bit is empty now, a shabby ruin. I do not wish to stay.

But all this is ahead of my story.

My first memory is of being hastily

snatched from the woolen carpet covering the nursery floor of the Salem house

and my nurse saying crossly, "You naughty girl, you are much too old to do

such a thing." Three,

perhaps? The curtain is hastily

drawn again. The next memory is a flash

picture of my mother, father, brother and me standing by the glass doors

leading to the garden. In my father's

arms is a small black cocker spaniel puppy.

My father (or mother) is saying, "How about Captain Sigsbee for a name?"

(The battleship "Maine" had just been blown up.) So Sig or Siggy it was until he died, an

elderly gray-chinned admirer of my father.

Beginning with the summer when I was

four years old in 1898, memories come flooding fast. Life really began then in the freedom of a

White Mountain valley, Waterville Valley, where my family went for a month's

vacation. I must have been like an

ecstatic puppy, so joyful and so real are those memories. I discovered an unbelievably beautiful world

of enclosing mountains, wild rushing river, myriads of pollywogs, captive

little green snakes, a sandbank chute,

prize red pigs, white fairy Indian pipes, unblemished white

fungi, mysterious forest trails, and most of all the four-horse stage which

brought passengers, baggage, supplies and mail fourteen miles up into the

valley - the only contact with the outside world. Then and there began my passion for any and

all kinds of Horse.

In short order I made friends with

the driver - a shadowy memory now, but I think his name was Alec. Whenever possible thereafter, I greeted the

stage at the hotel when it stopped to discharge its passengers, climbed up

beside Alec who would let me take the reins and with his guidance drive the

horses to the stables. Some years later,

when I was nine years old, I won over the driver of a stage -coach in the

Scottish lake district who allowed me to sit beside

him all day long while the Scottish mist dripped from our hats and even ran

down our necks a bit.

We went to Waterville for two summers

but memories merge here. I remember stepping into a yellow jackets' nest in a

ditch and (plastered with cool mud) lying in the porch hammock of our little

cottage while people came to sympathize.

I remember the horses of the stage starting unexpectedly while I was

climbing to the driver's seat, my falling and thinking the heavy wheel had run

over my leg. I now doubt that this was

so since my leg was only bruised. I

remember that my knees were in a constant state of rawness from my falling down

on the gritty gravel paths of the valley.

But these disasters only pointed up the joys of this Golden Age. Other memories of other

years are of happy, interesting, important

times but they remain in a dimmer light beyond the focused clarity of those two

mountain vacations. Waterville became

my Arcady with or without reason, probably because I

did not return there until I was grown up.

Last summer, at the age of nearly seventy, I returned for a few

days. I took the trail of a mile or so

to the Boulder, a famous huge fellow around which the Mad River flows. (I have a faded photograph

of Theodore and me in 1899 standing in front of its sheer face with the water

of the river flowing about our legs.)

Sitting now on a rock I removed my sneakers and socks and dabbled my legs up to the knees in the cold mountain

stream. The music of the rushing river,

the song of a white-throated sparrow, the water swirling about my legs, the

smell of fir balsam, the sight of delicate pink wood

oxalis nodding above the river bank gave me a sudden sharp stab of

recognition. I was a child once more for

a few moments, passionately embracing the natural world with all the warm

emotion of the one-time five-year-old.

"You surely have come full circle," I smilingly told myself.

When I was five - or was I just six?

- Father bought five acres of land and a large white house built about 1820 at

the top of a hill in that part of Danvers called Putnamville. The house and lawn were shaded by stately

elms which edged the property. Standing

on the banking (as we called it) you could follow the road with your eye down

two humps of the hill to a bend at the bottom where the road began to lead

straight as a string across the plain to the town.

Along the plain were then scattered

two or three farms and three or four pleasant, more distinguished houses where

now there is an endless row of suburban homes.

The situation of our house was of real importance, for from the

embankment you could watch the straining of both carriage and work horses

toiling up the hill. Up this hill also

came herds of cattle and flocks of sheep on their way to a slaughterhouse a

mile or more away. I remember many times

trying to plot the kidnapping of one of the little lambs following its mother

to its untimely end, but I was never able to carry through the plan. I remember

being specially fascinated by a whistling work horse which frequently went by

and which had had a tracheotomy and now breathed through a metal button

inserted in its neck. Then there was

Colonel Appleton, an elderly, mustachioed, pith-helmeted man of great military

bearing, who used to ride by on his handsome dock-tailed horse. I was particularly angry with people who

docked their horses' tails, but Colonel Appleton only amused us. The horse's tail was bound to the end of his

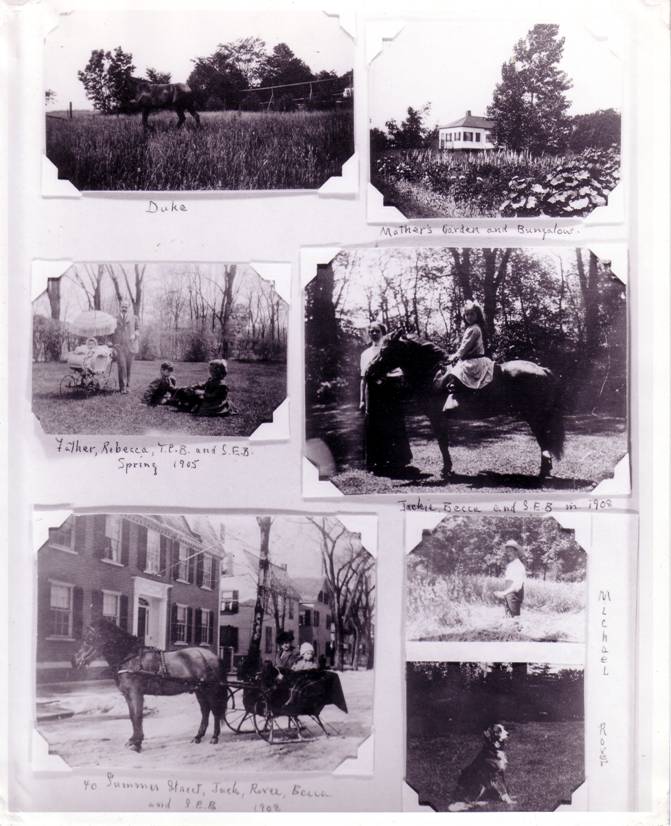

riding-crop which he continuously flecked to shoo the flies away. On this banking good dog Rover, of setter

extraction, would patiently sit waiting for the return of horse or pony or,

later, the chugging automobile which would bring his family home.

Up this hill, also, very slowly would

come the country trolley car once every hour, occasionally in the fall, because

of fallen leaves, unable to make the grade without the motorman sanding the

tracks, shovel and bucket always being kept

on the front platform of the car. In

blueberry time the cars would be swarming with people, young and old, almost

everyone provided with a shiny metal bucket. At the end of the carline, a mile

or so away, they would scatter into the pastures for the day, returning on the

cars late in the afternoon with pails full of blueberries and with small children

asleep in their arms.

Father and Mother made immediate

alterations to the newly acquired property.

The fence along the road was replaced by a border of shrubs. The barn was detached from the house, moved

back, and changed into a useful stable and carriage house. A wide veranda was built outside the

dining-room, which opened onto it through French doors. Vegetable and flower gardens were laid out,

vines and trees were planted, and later a tennis court was built. But that first summer there was no bathroom.

All day long I lived at the well-kept

dairy farm across the street. It was

owned by a Mr. de las Casas who loved the old colonial house, in which he

established a tenant farmer named Mr. Landers, and to which he would frequently

come. Mr. and Mrs. Landers as well as

Mr. de las Casas became our

friends. No one could have been more

patient with children than Mr. Landers and his hired man, Roy. I followed them everywhere like a dog. I rode on hay loads, corn stalks,

manure. I rode on the field drag, behind

which clouds of dust rose to settle on our bodies. I followed the plow and rode the plow horse.

I helped remove stones from the fields. I fed hens, drove in the cows, pitched hay

down the horse mangers, and when all was finished sat in the sun in the great

barn door fondling Gip, the bull dog, and the

numerous barn kittens. Then it would be

time to go home. My mother soon learned

to accept the bodily condition of her child. During that

first summer, each night I stood or sat in the laundry tubs (which were piped

with running water) while I was shampooed and scrubbed and made acceptable once

more. Soon my attire became

nothing but sneakers and overalls, and for two or three summers I lived in dirt

and bliss.

On hot days Theodore and I would

bring down the old fashioned "tin hat," fill it with water from the

hose, after placing it at the foot of the sloping bulkhead door which we wet

with the hose to make it slippery. Then

we would slide down the door to splash into the cool water in the old tin

hat. This was splendid fun.

Father was sweetly trusting and

gullible about horseflesh and used to pay much too much for what always seemed

to turn out unworthy. Our first horse, a bay, was bought from our Salem

grocer. We owned him for only part of a

summer, for he was as slow as a snail and also was a balker,

sometimes refusing to budge. The next

horse was a tall long-legged gray. He

covered the ground well, but when he had recovered from the boredom of being a

delivery horse, his spirits became so high that he developed the trying habit

of kicking to free himself from carriage and

harness. Father bought a heavy kicking

strap but

even then his heels were on display too

often. This horse gave Father and me a

fright one day. We were returning from

Salem. Going downhill Gray fell down and

began to struggle to get free. Father

jumped out and sat on his head while I freed the harness from the carriage and

backed the carriage away. From then on I

was certain I could be master of the Horse.

But our next horse and the next I could do little about. They both were very pretty, but the bay with

a double mane and thick tail was a stumbler, and the

white one, though a good roader, used to crib,

filling her stomach with air which gave her colic. Dan used to pull her to her feet, jump on her

back and make her run until her stomach ache had subsided. A wide strap around her neck seemed to do no

good. Next came

a bay named Mabel which Father bought from a friend of Mr. Landers. Mabel was

sure but slow and disappointingly unexciting.

When it was time to buy the next

horse I knew more about horseflesh than Father did. I was nine or ten when a beautiful bay was

brought for inspection. He was a bit

chunky of body but quietly spirited, eager and gentle. I prayed "Please," and Father said

"Yes." We named him "Duke" and we loved him for years, even

turning him into a saddle horse when I had outgrown my pony. He and my pony became inseparable

friends. I used to slide down his hay

chute to talk to him and to stroke his nose, and he always seemed glad to see

me come.

By the time of the First World War

the automobile had largely crowded out the horse and buggy. I grew up with the automobile just

as my children grew up with the

airplane. Ours was one of the early cars

in our neighborhood, bought in 1906, but it was a second-hand 1903

Cadillac. It was a one cylinder car

which looked for all the world like a fussy old lady

with bustle and parasol. Its back seat

rose above the rest of the car like a throne.

It had side entrances rather than ones through the rear like some, but

no doors and no windshield. It was

covered with brass - brass trim, brass side lamps, brass search lights, brass

levers, brass horn. It was not reliable

because of frequent flat tires and slipping clutch,* but for the first time we

were able to see what was beyond the five or ten mile radius of our known world

away from train and trolley tracks.

My early world, then, was very small

and intimate. It seemed peaceful and

secure. You absorbed the belief of your

parents in the long sure upward progress of mankind. You had not the slightest inkling that you

would be married in wartime to an army officer.

War and torture the human race had outgrown. Life was like the slow meanderings of a

placid meadow stream; there were no rapids.

Possibly it was a bit dull for grown-ups but I hardly think so. Conversation, reading aloud, music, friendly

visiting, games prevented that, and in the winter

community interests absorbed much time.

As I look back at my parents' friends, I think of them as remarkably

interesting

* Theodore says it was driven by a

long chain similar to a giant bicycle chain.

I remember that now, and I remember the gigantic heaving of the car

prior to putting it in gear.

people, most of them alert and

knowledgeable in one way or another. In any case, life was surely never dull

for me, a child. One had time to claim

kinship with Mother Earth, to learn to know her and love her, time to find what

eyes could see and ears could hear and nose could smell. You braved the elements in long woolly

under-drawers and high skating boots which I do not recommend, for my legs were

chapped all winter. Our wool gloves

never covered our wrists properly so that they always were rough and red. The

only leggings available in those days were black knitted tights which you wore

under your skirt and tucked into the tops of the shoes. These and the long underwear often were soggy

with melted snow. Ski trousers had never

been thought of and would have been unladylike, anyway. How foolish all that

seems this present day! You tramped for

miles with skates or sled or toboggan.

You walked long distances to school, even with eyes and nose adrip, in sun, rain, snow and icy winds. You were as undisturbed, undistracted and

free as a young colt in spring. You were in reality a young animal taking life

and all it had to offer for granted - all this until adolescence brought the

slowly dawning consciousness of the uncertainties and burdens of adulthood.

In Putnamville

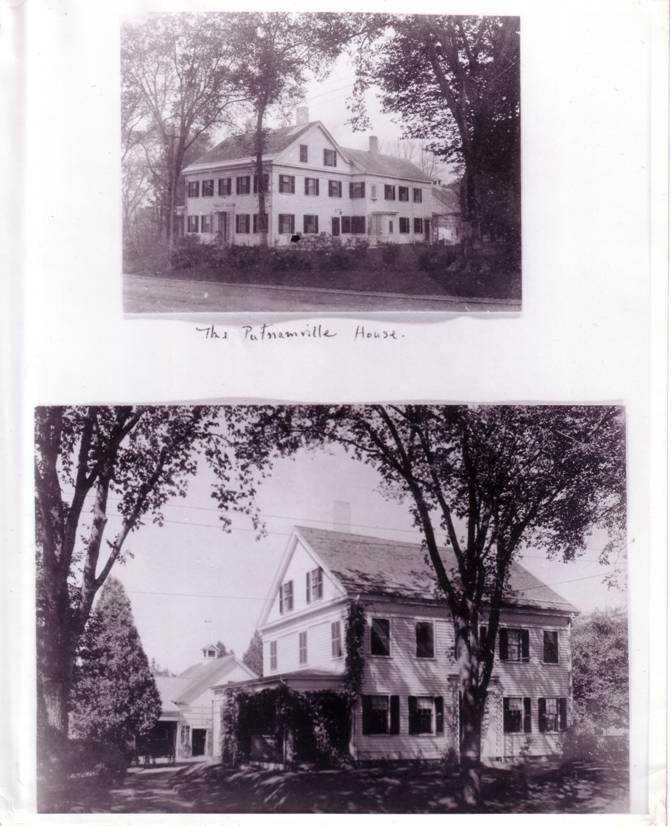

a lane ran along the side of our property to the house where the Lovelaces lived.

They were an elderly couple, country folk, who had bought or inherited

the house which had once been a colonial homestead. The lane was canopied by our wineglass elms

and a beautiful old white birch. It

looked like a grass-grown

country road, and a stranger turning into it

by mistake would find that it completely circled the house and led him quickly

out to the main road again. On our side

of the lane was our lawn and the hay-field of timothy

grass growing taller and thicker than I have ever seen elsewhere. On the other side of the lane were woods

partly concealing an octagon house (we called it "the inkwell") in

which Mr. Jodrey lived, who knew more about poultry

than anyone else we knew. My brother and I, when we

were old enough, would buy his Silverlace Wyandotte

eggs and hatch them under one of our broody hens. Later we changed to Rhode Island Reds which

were better layers, but I considered this a great come-down in our association

with hens. The Wyandottes

were so distinguished looking that we used to name them for people we knew, but

the Rhode Island Reds never seemed worthy of that honor.

A path from our house through the

hayfield led to a gate in the wall opposite a door of the Lovelaces'

house. I never saw anyone use this door,

but it was impressively guarded by two wooden dolphins about four feet high

whose scales and teeth were all carved from one piece of wood. They stood on their chests with their tails

flung up in a reversed letter "S," so that their open mouths were

close to the granite step on which they rested.

They were painted dark red with appropriate colors for eyes and tails

and I think each carved scale was outlined in a lighter shade. At either side of the doorway tiger lilies

grew. I loved looking at this doorway;

it seemed

Oriental to me and I used to wonder if I should ever go to

China.

Mr. and Mrs. Lovelace were very

elderly and quite uncommunicative, but they were always kind and tolerant of

us who, I am sure, were rather annoying at times. They used to sit in a small summer-house near

their picturesque well with its little roof and its bucket drawn up by turning

a handle, winding the rope neatly around the thick wooden spindle. They always seemed to have leisure, though I

fancy their labors were done before I had left my bed. For Mr. Lovelace had a very good vegetable

garden in the pasture where he kept his cow, half an acre or more completely

encircled by a stone wall. There must

have been a gate leading into it, but I do not remember one. There was also a well-kept outhouse which

fascinated me because we had a bathroom.

The Lovelaces were generous with its use and

never told me to go home when I asked to go there. I liked the wallpaper samples and pictures

from calendars pasted on the walls. I remember particularly a bright pink

complexioned lady with a very short neck swathed in pink tulle who was wearing

a large red rose behind one ear.

The house was an old New England

homestead, well proportioned and well built. It was one of the oldest in the

neighborhood, though friends of ours lived about half a mile away in a splendid

old lean-to built at the very end of the sixteen hundreds; and the farmhouse

across the street was lovelier, and probably older, with the old fireplace, its

oven, and paneling in the downstairs rooms still intact. An out-

side flight of stairs led to a door in

the upper story of the Lovelace house, and there their widowed daughter lived

with her two sons a little older than I.

I liked these boys very much.

They were gentlemanly and well-mannered and never bothered us when we

did not wish them around. Roy I liked

particularly. He was always helpful when

I needed aid in catching my rabbits or finding the chickens. His skin tanned in

the sun each summer to a lovely biscuit brown. But I think it was his feet

which really fascinated me because his toes added up to the sum of twelve. His brother I thought a little pert. He had a turned-up nose inclined to

freckle. He would stand aloof, hands in

pockets, with a half humorous, half quizzical expression on his face. Still I liked him.

A wide gate led from the lane near

one end of the house into the larger pasture.

The Lovelaces rented this land to Mr. McCarthy

who lived a half a mile away. His son

was station master of our tiny local flag station where bright flower beds

tended by him won prizes from the Boston and Maine Railroad. Every morning and every evening Mr. McCarthy,

driving his old cream-colored horse and trailing two or three cows behind his

cart, would come and go from this pasture.

He was a taciturn man and I who worshipped all horseflesh, especially

cream-colored horses, asked him only once if I could ride with him. His horse was too old to walk faster than the

cows. It was a leisurely trip and I

wondered what Mr. McCarthy could be thinking about during his silence. Finally I asked, "What makes those

patches on your horse where there is no

hair?" Mr. McC.

replied with one word. "Moths,"

he said, withdrawing into silence once more.

Before long I was familiar with all

the wood-paths, brooks, the hill where high bush blueberries grew and on the

top of which the Judge Whites built their cabin. I could even find my way to Oak Knoll, where

Whittier had lived with his cousins in his latter days, through the woods a

good three quarters of a mile away. But

I did not need to stray so far afield with so much of

interest right at hand and with a three hundred acre farm across the road. I remember particularly the excitement I felt

one day near Mr. Lovelace's vegetable garden, where I was cutting a barberry

branch to make a bow and arrow. Suddenly

I noticed a partridge not six feet away, sitting quietly on a low limb of a

small tree. We knew we saw each other

but each of us waited minutes for the other to make a move. She held out longer than I. I had the same experience at other times with

a quail, a yellow-billed cuckoo and a scarlet tanager. I think these meetings were the beginning of

my interest in birds. The elms were a

great attraction to the orioles where they built their deep, swinging

horse-hair nests high above us. Their

lovely song still makes my heart leap up.

They always arrived on May tenth, my mother's birthday, - or so we

thought.

At one time we had, among many pets,

a tame crow named Jim. He was found by

my brother and George Benson while still a nestling. He used to sit on a limb of one of the apple

trees, ducking his head and

hunching his shoulders each time a pair of

outraged vireos, who were nesting there, zoomed down in quick succession, just

missing his head. I remember his

enormous appetite, for we had to feed him before he could fly. He would sit on our shoulders pecking away at

anything bright we were wearing and talk to us in soft, gutteral

sounds. One day he was missing. Auntie had seen a boy go up the road with a

basket on his arm quite early in the morning but she had thought nothing of it. Jim never came back.

We always had some project

afoot. For a while Theodore was interested

in the various creatures we tried to raise:

chickens, guinea fowl, pheasants, ducks, geese, pigeons, rabbits. The pigeons were strictly his; the rabbits

were mine. We cooperated on the others.

One summer we raised three white geese, the story-book kind. One of these became madly attached to Auntie

who often would sweep up the grass clippings and leaves on our lawns. I wish I had a photograph of this little old

lady (she seemed old to me) dressed in black, looking a good deal like the

elderly Queen Victoria, carrying her broom around, always followed by the

softly gabbling goose. She was ten years

older than my father. She had inherited

the Broad Street end of the Salem house with my father and always lived with

us. My father died in 1911. She died of cancer a year later.

Two or three years after my father

and mother were married in 1891 they purchased the Summer Street end of the

house from the other heirs, changing the old house once more into a single

home. This

was the

oldest part, built in 1762. It had, and

still has, a beautiful front hall and staircase. These and the mantel in what we called

"the music room" are all of McIntire design. The front doorway is often reproduced in books of photographs of old Salem houses.

Aunt Alice always lived in the Broad Street

end of the house, though she had meals with us.

Theodore and I, I am afraid, were not always kind to her; she seemed queer to us in contrast to

our beautiful young mother. We loved to play practical jokes on her in an

effort to upset her fixed habits.

I often wish I could tell her that I

really loved her because she was always kind and generous to me. She it was who

gave me a large azalea every birthday down through the years, and saw to it

that it was at my place for breakfast. I

should have missed it sorely had it not been there. She gave me my large stockinet doll, my

riding boots and half of the pony and cart I had so longed for. I never went into her bedroom, and only went

into her sitting room when invited.

Sometimes I slept in the big double bed there with a stiff hair mattress

and a soft feather bed on top of that.

In the morning the feather bed would be removed and the hair mattress

thrown over the footboard, making a tunnel through which I loved to

crawl.

This room was full of fascinating things from a child's point of view: onyx

paper weights, figurines, an iron donkey which threw a little darkie-boy over

its head when you pushed a button, a mahogany board holding beautiful colored agates

which I played with by the

hour. A

large engraving of the Madonna of the Chair hung over the bed and on another

wall an engraving - perhaps a Guido Reni- of Christ

wearing the Crown of Thorns with drops of blood running down his agonized face. I remember, also, little treats of a navel

orange and a piece of sponge cake, and of

sitting - or trying to - in her slippery lap, too stout to hold a child

comfortably, while she read me children's stories from the Christian

Register.

Her bedroom upstairs in the third story was so full of possessions of

sentimental value that we never once went beyond the locked door. She had a dressmaker and a seamstress come

regularly who made her handsome voluminous black or gray taffeta or satin dresses, always

trimmed with ruching, lace and sequins, the bodices

painstakingly

boned and lined. Many of these she never

wore, but when she was

dressed in one she looked very impressive, handsome and Victorian, I associate the making of these with a certain

embarrassment. Miss Parsons, the

seamstress, used to use many needles threaded with basting cotton, one after the other. One day I asked if I could help her thread

her needles. She gladly consented. After much effort on my part I carried to her about a dozen threaded needles only to

receive a round scolding. I had

carefully tied a knot in each thread at the needle's eye, as we were shown to

do with wool in our kindergarten. I

never offered to help Miss Parsons again.

Auntie wore a false piece on her front hair in

the morning while her sparse but pretty soft white hair was being crimped on

hairpins underneath. I never saw her use it in the afternoon. She was always late to meals, annoying all of us, especially Hannah,

the cook, and Ellie, the

"second-girl." She had to have

special dishes prepared for her because she would not touch many of the foods

the rest of us ate and liked. It must

have been very hard for Mother and I am sure Father was many times

pulled apart by split loyalties, rather

sadly.

I think of my father now with enormous respect. His kindnesses were myriad. My mother's family said he was the kindest

person they ever knew. He never failed to

help where help was needed. He had cared

for his two invalid parents for years, was tied to an eccentric older sister who

depended upon him for everything. He

tried to keep the family peace, took my mother's family into his home so that there

always was a Crowninshield aunt or aunts or

grandmother there, helped to support them (for Grandmother Crowninshield

was left a minister's widow with five young daughters when Aunt Margaret was

only six months old), paid for Aunt Margaret's education at Wheaton and for the

singing lessons (she sang beautifully), ran two large houses systematically

and carefully, took his useful place in the community, tried (oh, so hard) to

be a good husband to an intellectual wife not so well endowed domestically, and who was

fifteen years younger, tried to understand a gifted, rather wilful

son and a carefree, unseeing daughter who did not yet comprehend the burdens he

bore. He finally broke down in what was

then called nervous prostration, a terrible

two-year illness slowly developing before that. He finally took his own life. My heart is wrung with the thought of the

help denied him but available today.

But I must finish about Putnamville. How can I shorten this and yet tell all I need to tell?

I

think a very special joy was the drives with the family after supper through

the peaceful, darkening countryside, sitting beside Father on the front seat of

the commodious carry-all, with only the light from the carriage lamps, the

flashings of fireflies, and sometimes moonlight sifting through the trees to

light our way. Then there were trees to be

climbed, apples to be tasted - a dozen different

varieties - the ridgepole of the barn to be assaulted (Theodore climbed the

cupola, but I never quite dared), the large arborvitae trees to hide in, the

barn loft to play in, the swing, hammock and parallel bars to do stunts

with, the great Norway spruce to be scaled with

thumping heart and ruined clothes and Stevenson's "Up into the cherrytree" running through my head. I had to climb until "farther and

farther I could see," way above the barn and lower trees until I could see

the church spire in Danvers a mile or more away. Another great joy was Rover. He had been given to Theodore, a ball of

long soft fur when about two months old and I was nine, but from his arrival

on July Fourth, when he and I were somewhat timid of the fireworks Father always displayed for friends and

neighbors, we were

inseparable

partners for years and years.

The one drawback of being near a dairy farm was the swarm of flies we

had to contend with. We had flypaper

everywhere in sheets or in hanging curls.

Sometimes these would be quickly covered with flies. One of our half-grown kittens sat on a piece

of flypaper one day and then

ran wildly across the lawn with it sticking to her rear. All we could see was a sheet of flypaper, with a

tail waving above it, rushing away.

We had to remove the stuff with kerosene.

Those flies, I am sure, were responsible for

a serious illness I had when

I was seven years old. It had been a

very hot day in late July. The Gortons had

come to play with us and we played Run Sheep, Run hard until our heads

were soaking with perspiration. To cool

off we climbed an apple tree and tasted the

apples which were far from ripe.

After supper I went across the street to sit with Mrs. Landers in her lawn swing.

Suddenly the world began to spin around me and I felt horribly

ill. I stumbled home on wobbly legs and

remember nothing more until I was conscious

of being in my mother's bed with a nurse all in white bending over me. The doctor called it dysentery. It was

during this illness that Dr. Kittredge, our beloved

Salem doctor, bought his first automobile

and Father had our first telephone in the country installed. I remember that the number was "seven,

seven, ring eleven" (you said it that way). It was a clumsy looking instrument screwed to

the wall with a crank to ring "Central." Almost the first message which came over it

was that President McKinley

had been shot.

This is my impression, anyway, though I have not checked on the dates. I was a starved little girl not able to take

anything at first. I remember how good

the warm milk toast and the broth tasted,

when I finally could take food, and especially the sherbet which Theodore made

for me each day in a tiny ice cream freezer.

Then one day my naughtiness returned.

I got out of bed and ran on very wobbly legs through two or three rooms

before the distracted nurse caught me and carried me back to bed.

One day during the next summer I went with Mother through the blueberry

pastures to Mrs. White's hill where she had invited her sewing

"circle" to a picnic lunch.

The Whites had built a pleasant cabin with benches outside around an outdoor fireplace, and there

the Salem ladies settled down. I knew

that there was a handsome year-old colt which roamed that hill, unbroken but

gentle enough. It had long been my desire to feed him some sugar while I

petted him, all of which I did. He insisted on following me when I started

back to the camp. It never

occurred to me that the ladies would not be delighted to see him. When the colt and I arrived

in the clearing there was a mad scramble for the cabin. Mrs. White flashed daggers at me so the colt

and I went away. I think I went home

rather than to face more disapproval.

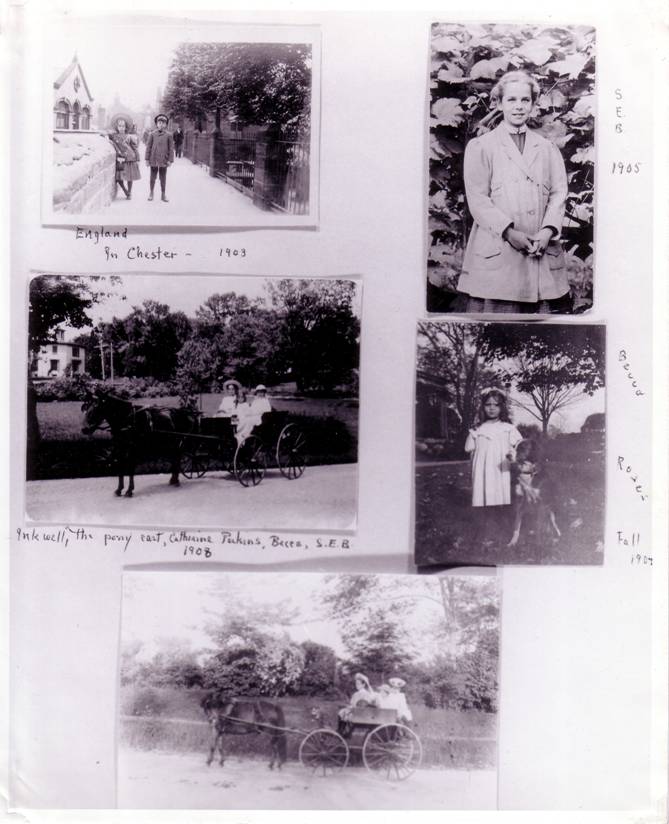

I had dreamed of owning a pony for years and told so many

people that I was surely going to own one

some day that I think that made it come to pass. How well I remember that fresh June morning

when I

woke to realize that my own pony was in the

stable. I was eleven years old. I had dreamed of brushing him and braiding

his tail and mane with ribbon and then taking him out to munch green

grass. I rose very early, took Jackie

(he was named before we bought him) by the halter rope down to the timothy

hayfield, feeling sure he would henceforth follow me with gratitude like my beloved Rover. No sooner had

we reached the field than he wheeled around, kicked me soundly in the stomach and went galloping away. Tears stung my eyes, but then my ire rose,

and from that day on we had constant battles over balking, over trying to throw

me, over watertroughs, over anything he wanted to do

and I did not. He was a beautiful little

beast, half Welsh, half Shetland, with

an indomitable spirit which I learned to respect, admire and love. Riding

or driving him, I would follow behind

the family carriage. He insisted upon

staying so close that often he would

bump his nose when Duke came to a sudden stop.

But he never would do

otherwise. His real affections were

centered in Duke whom he loved with

all his loyal, worshipping small heart.

I

had a few chores to do, picking strawberries, cutting sweet peas and roses for the

house, helping to shell peas, caring for animals,

making beds. Occasionally Michael would

be too busy to cut the lawns and we would be asked to help with them. One time a bit disgruntled at the thought, I

harnessed my pony to the lawnmower. Everything went very well until we hit a

snag. Jackie started to run with the

mower banging at his heels. First one

trace broke and

then the

other, freeing him to dash wildly away.

Fortunately no real harm was done, but I never tried that again.

After I acquired Jack I bought from Carter White a Spanish nanny

goat, a pretty creature with a little harness and a two-wheeled cart. I have a photograph of Rover sitting on the seat

with a cap on his head while small Bunny Putnam holds the reins. But pony eclipsed Nanny, although I had them

both for some time; in fact Jack was a member

of our family until he died in 192 9 when he was about twenty-seven years old.

He had been passed on to my sister when I grew too old for him. After that, children of friends used him for

a while. Finally he gave our own children a few summers of fun, though by that

time he was no longer handsome or spirited.

Theodore, as I said, was always inventing and

building. I remember particularly a

kind of cable car and a roller coaster.

For the cable car he ran a stout wire from rather high up in the Porter apple tree down to a lower limb of a tree

some distance away. On this he had rigged a block with two wheels or pulleys

which could travel along the wire.

Through the block he bored a hole and attached a rope, two or three feet

long, which held a short horizontal bar or seat. We would climb the tree, straddle the bar,

hold on to the supporting rope and let go. The resulting ride was short but quite

breathtaking and most successfully exciting until our parents persuaded us it was not safe.

The next experiment

was a roller coaster which he built with the

aid of his friends - a wooden track running from

a platform to which we climbed by a short ladder to enter a two-seated wooden

car. Down we would go with heart in

mouth, the chief trouble being that the car often came off the track giving its

passengers bumps and bruises. Our

parents persuaded us this also was dangerous.

As we grew older Theodore's friends came more and more often. Rifle

practice became their sport, with a target out by the tennis court. I was not in that group very much but I

practiced with Theodore's rifle and one day shot a red squirrel in the top of

the black walnut tree. I was so

disturbed and amazed that I had actually shot him that I think I never shot at an animal again - until

recently when I shot a rabbit here in our

Belmont garden. I took the little dead

creature to Michael, our handyman and friend, and asked him to bury it for me.

The boys were beginning to be mischievous

adolescents. One Saturday in the fall, late

in the day, they greased the electric car tracks most of the way up the hill. The poor motorman was desperate, got out of the car and endeavored to round up the

culprits. I had not participated but I

warned the boys that the motorman was on the lookout for them, that they should

be innocent looking and not get caught.

I think they were really afraid that the police might investigate. They never bothered the carline again.

Except once, when my cousin Faelton Perkins was visiting us. We

thought it would be splendid fun to make a dummy and stand him beside

the white post.

This we did one evening, putting a joss stick in his mouth and tying a

rope around his waist which we strung over a limb of an elm tree above. When the

car came up the hill it stopped for the supposed passenger to get on. Nothing happened so the motor-man leaned out

to investigate. It must have dawned on

him that the figure in the dark was a dummy.

In any case, when the car came back the motorman was ready, leaned out and

tried to hook the dummy with his switch stick.

But we were also ready. We were

lying on our stomachs behind the hedge with the rope in our hands. Theodore gave the rope a tremendous pull; the

dummy flew up into the elm tree and both motorman and we gave a roar of

laughter. The motormen and conductors -

there were only two of each - were really our friends, We rode with them to

Salem and to school each spring and fall.

I wish I could remember their names.

I am sure Theodore can.* One

motorman was

very jolly, always cracking jokes about "Punkinville"

and playing Yankee Doodle on the bell which he banged with his foot. Was there ever more fun than sitting on the

front seat of an open trolley car driven by a friendly motorman?

There were not many children near at hand to

play with except Roy and

Webster Blanchard, but Mother was very good about letting our friends come to visit. I remember many giggles and night-time talks

in the big painted bed in the downstairs guest room when Rebecca

![]() Two of the four were Mr. Lyle and Mr.

Porter.

Two of the four were Mr. Lyle and Mr.

Porter.

Pickering or Kitty Pew or some other girl came to visit me. But there were many interesting grownups in the

neighboring houses who often came to our house to spend an

afternoon or evening to talk, take a drive, or to sing. I remember the pungent smell of cigar smoke

drifting into my bedroom while the grownups sat on the wide veranda below my

window, the men smoking and the ladies twirling joss sticks to keep the mosquitoes

away. At the foot of the hill, Mr.

Watts, a delightful Englishman, and his humor-loving New England wife had built a

charming house full of interesting mementos from his wide travels. He and others would come to sing while Mother

played

the piano. My Crowninshield

grandmother had a good voice. Mother has told me that she sang in this group also, but I

do not remember

it because pernicious anemia made her an invalid when I was still a little

girl. I barely remember her when she was

active and well. The Whites, the Wattses, the Fowlers, the Misses Lander - Salem ladies who

bought the house half way up the hill - were frequently there. The Lees, the Brookses,

Professor Morse as well as other friends came often from Salem.

I remember well one evening, when I was sitting just inside

from the covered front porch, that a bat lighted on my

arm. They say bats do not bite, but his hooks gripped and I,

terrified, let out a murderous yell. I

remember Professor Morse dashing in from the porch terribly concerned, and shouting,

"Good God, what's the matter? A bat, is that ALL?"

Mr. Frank Lee - Francis Lee - was a great wag. He was always chuckling over his own numerous amusing experiences. He could imitate sounds of animals and birds, invent spur-of-the

moment riddles, tell exceedingly tall stories to a delighted audience. I remember one evening a group of friends

were sitting on the wide veranda which overlooked the lawn and Mother's garden. The white phlox shone in the moonlight. Mr. Lee asked, "Why are the Brownes like the Bethlehem shepherds of old?" A long pause. "Because they watch

their flocks by night." His sister was Alice Roosevelt's mother. When Alice was married to Nicholas Longworth Mr. Lee came

back from the White House wedding with a long amusing story about his borrowed

top hat; and after going to England he circulated among his friends a

photograph of himself and Queen Victoria having a cosy

tea together - a trick of blending two photographs. One day we took him to see the big dairy barn nearby.

The farmer, who kept no pigs, was quite excited to hear one grunting in

his barn. He was rather disappointed, I

think, to discover Mr. Lee instead of a pig.

My memory of the Misses Lander centers around one event. They were rather

elderly, intelligent, musical maiden ladies of the old school. I thought them

rather forbidding, but I think now they were merely shy with children. Mother was very fond of them. One day they came to call. That was the day I chose to be rude to my

mother in front of them. I cannot

remember what I said, but it was bad enough to embarrass my mother.

Children then were supposed to treat grownups with

great deference. After the ladies were gone Mother talked to

me very

seriously. She told me I must go down to

the Lander house to apologize to Miss Helen and Miss Lucy for my rude

behavior. (I probably was eleven, or

possibly twelve.) That was one of the

hardest things

I have ever done. Miss Helen Lander came

to the door. I blurted out my

apologies to her with Miss Lucy hovering in the background. I think they tried to hide their smiles. Anyway, I was sent home with a cookie.

Before long the carefree days were

over. Since my sister was born when I was ten, I

was cautioned over and over to be quiet, to learn to be more thoughtful, not to bang

around so. Almost for the first time I had to

consider others. I was growing up. Later Father's illness caused a pall to hang

over the family, voices became lower, friends came

less often. Finally one day in May,

1911, when I had gone to Pittsfield for the weekend to visit Anna Hathaway at

Miss Hall's School, Father took his own life.

After that, life was never the same.

Soon Hannah, Ellie and Michael all left us because it was not the same

for them, either. They had loved

him. Mother let me buy a polo pony with

money I had earned barreling and selling windfall apples. We stayed in Putnamville

that summer, but our hearts were no longer there.

Mother, more crushed than we knew, was lonely and restless. She decided to sell the house, send many of

the things there to the Perkinses in Bridgewater and spend

the summers with them

for the present.

That fall, with the aid of a young lad, I drove over the road with the horses to

Bridgewater where Uncle Charles used them to drive to and from work. A young fourteen-year-old, named Walter, who

was trying to fill Michael's place, led Texas, my polo pony, while I drove

Duke. Walter sat, with legs dangling, on

the back of the one-seated run-about. We

went by the way of the Salem-Lynn turnpike, across the marshes, through Revere,

Charlestown, past the North Station in Boston, all along Tremont Street,

Columbus Avenue, Blue Hill Avenue to Milton where the horses were put up for the

night. In Charlestown Duke, terrified by

the elevated trains thundering above us, sank spread-eagled flat on the

cobblestones, while Tex broke loose, wheeled up onto the sidewalk and nearly crashed

into the large plate glass window of a saloon before we were able to catch him.

Somehow we reached Milton

quite whole. Walter then returned to

Salem. Uncle Charles Perkins met me next day

to help me get the horses to Bridgewater. I was seventeen.

I have never forgotten driving our caravan

down Tremont Street past the Common.

Even then this seemed rather unusual.

I often think of this trip when I am shopping at R. H. Stearns's. Duke finally went to live with friends of

Uncle Charles, and the following year I sold Texas. Jackie remained in the family to give

pleasure to Rebecca and much later to our children and the cousins during summers at Chocorua. He died

old and tired and quite ready to go.

But Putnamville was only half of my life

and it became even less so as I grew older, for I began to be hungry for my

friends and looked forward with eagerness to

visiting them, especially Kitty Pew in Rockport. More about those visits later, for now I must

go back to early years in Salem.

How can I tell all I wish to without

becoming a frightful bore? I

shall put it on paper, nevertheless.

Our Salem house was altered during the summer

of 1900 after Father had bought the house in Putnamville. I remember it as it used to be quite well - the

inconvenient picturesque old kitchen and pantry ell, the inner windowless

room through which Pat, the furnace man, had to go to reach the cellar stairs

and where Theodore and I, alone at early supper, sloshed lemon jelly through our teeth

with giggles and joy. I remember the dining room which opened from it with soft orangy wallpaper and steel engravings of famous people on

its walls; the carpeted front parlors divided by sliding doors; the very steep

stairs leading to the third story. All

these were entirely changed, most changes for the better, yet I have regretted

that the kitchen ell and the dining room, as lovely and large as it came to be, had to

lose their eighteenth century character and become more of 1900 in feeling.

However, the front hall set the atmosphere for the whole

house. Its low stud, handsome paneling,

carved twisting balusters and wide hand

rail which swept around the open upper front hall in gracious

line, the arches of doorways and of the

upper hall window with its window

seat, remained untouched and quite perfect.

It is in my opinion, the more

beautiful twin of the hall in the King Hooper Mansion in Marblehead.*

The 40 Summer Street part of the house had

been the original part built

in 1762 by my great-great-great grandfather, Thomas Eden. He lived only six

years longer in which to enjoy his house, dying at the early age (it seems to us moderns) of forty-eight. A little later the Broad Street end was added

to accommodate various Smiths. (Theodore thinks the whole house dates

from 1762. I must check on this.)

Sarah Eden Smith, Captain Thomas Eden's daughter, lost her husband

Captain Edward Smith at sea as did her daughter, Mehitabel. The elder widow had her widowed daughter and

her little granddaughter come to live with her in the Broad Street end of the

house. Father said he was told that his

great-grandmother, who died in 1833, used to sit at the window hopefully

waiting for her husband who never came.** Mehitabel Smith had married a Jesse Smith of no relation

whose father, also Jesse, had

been a member of Washington's bodyguard.***

I remember Mehitabel's daughter (the little girl) as a very lame old

lady, Cousin

![]() The stair rail carving is identical with

that in the Derby Mansion.

The stair rail carving is identical with

that in the Derby Mansion.

**

Jesse Smith II, a lieutenant in the Navy, lost in the U. S. S.

"Hornet" in a hurricame in the Gulf of

Mexico in 1830.

***

Jesse Smith III, died at the Cape Verde Islands of yellow fever

in the

early 1840's. Frances Ver Planck has his portrait - a young midshipman in the U.

S. Navy.

Sarah Smith. She had been a

pupil of William Morris Hunt and was an excellent artist. She gave me some sketching lessons when I was

about twelve, but I was always afraid of her, probably because of her crutches

and her high cracked voice. Because I

bore her name she left me when she died in 1907 six dainty old silver spoons, six Windsor chairs, and one

of the bureaus her grandmother had had made for her two daughters, Mehitabel

and Sarah. Sarah was my great-grandmother. Her portrait, painted by Charles Osgood about

1838, hangs in our dining room. I have

told elsewhere about all this.

Father and Auntie bought the 40 Summer

Street part of the house about 1896 from the other heirs and turned the whole

into a single house. Auntie was once again

able to have her privacy in her own domain.

It must have been a tremendous relief for Mother and Father to be able to expand

quarters for their family. I was not

quite two years

old.

The house seemed very large to me, and

indeed it was with two front halls and its many rooms. It was a wonderful place in which to play hide-and-seek. My special hide-out was behind the flounces

under the

great four-poster bed* in the guest room.

There I used to hide when I had been punished or frightened or wished to

be alone or just to play a game. I

remember one day, when I was eleven, Father had taken Theodore and me to Boston

to see Ben Hur (I think). As we turned the corner into Summer

Street we saw an ambulance in front of our house.

Dr. Kittredge was waiting for our return to

have permission to take *Frances Ver Planck now owns

this bed.

Mother

to the hospital. As she was brought downstairs on a stretcher,

I fled to my secret hiding place, which I had

not visited for a long time, and it was not until I heard the horse

clopping down the street, taking my mother

away, that I realized she had had no goodbye from me. I ran like a hare after the ambulance crying

loudly. It stopped to let me climb up to

kiss Mother goodbye.

She had a ruptured appendix and was in the hospital three long months

at death's door. It was only by a

miracle that she lived. As I write these

words, it is only by a miracle that she is

still alive at nearly ninety-nine, again hanging on by that thread of

indomitable will.

The back stairs, after dark, always

filled me with alarm. I was almost sure

something was following me up those two flights of stairs to my room. I think this was caused by the two gas jets,

open flames turned rather low, which flared

and flickered making moving shadows on the

walls. The cellar, too, was a place

where evil lurked. This well could be where ghosts and witches

walked. Later the cellar lost its sinister aspect when Theodore's chemical

experiments were relegated to a little room there with a gay "T.C.B.'s Shop" painted by him in red on its

window. Another "T.C.B." still

exists on a window pane of the second story hall, engraved there by him with

the edge of a diamond.

I loved our front hall.

Theodore and I used to slide down the broad

banister much to Father's anxiety, I think, because of the beautiful

carved rundles, yet he never prohibited us from doing so.

(Long before the days of play-yard gymnastic equipment and jungle-jims,

he had built for us in Putnamville some parallel

bars, swings and gymnastic aids on which we played for hours.) I was well acquainted with the front hall. A punishment, which I never

minded, for being too strenuous, noisy or

unruly was to sit on the stairs for five minutes. I could time myself by the grandfather clock*

whose smiling friendly face I learned to know well and whose loud tick-tock

counted off sixty seconds of each minute.

This clock told the phases of the moon so that sometimes a full moon's

jovial face would smile down on me.

Father, before church every Sunday morning,

would wind up the two great

weights in preparation for another week of ticking seconds. All the clocks in the house were wound then, and

all the clocks would announce the hour and half-hour in various voices, deep

like the grandfather clock or tinkly like the black

marble and bronze ones in parlors

and library.

I loved Sunday morning.

Somehow everything seemed a little different - polished shoes, best clothes, Father in his cutaway and Mother

often supervising the dining room for expected dinner guests. Even the chirping sparrows outside sounded

differently, chirping against the church bells.

Sometimes I would go to church, probably not so often as I think

I did because we always went to Sunday School from twelve to one o'clock, but I liked church

better. Father, with

![]() *Now owned by the Bradfords.

*Now owned by the Bradfords.

his silk top hat and cane and Mother holding up her best long

skirts, which otherwise would sweep the

sidewalk, made me feel proud and important.

I must have wiggled a great deal - in fact my baby name was Sally Wiggles - because there would always be

made available pencil and paper to

keep me quiet. Father was a warden or

deacon, and later Aunt Margaret was the soprano of the choir, so I felt the North Church was very much our church. Carey and I went to a service there last fall after many years and I was

again thankful that the rather beautiful and unusual 1830 Early English Gothic

church had been among my early

memories. We treasure the thought of

having been married there.

I went to kindergarten, and later to school,

at Miss Howe's. Classes were held in one large room on the

third floor of Hamilton Hall, now the supper

room. This is a happy memory. Miss Howe commuted from Boston every

day. She was a born teacher, strict,

fair, rather modern in her choice of curriculum, homely with crossed eyes,

short, straight backed, apt to wear bright green or red flannel shirtwaists

with flat brass buttons, a broad belt from which hung an ample purse-bag, over her heart a gold watch hanging from a watch pin, and over her ear a gold chain

attached to her gold glasses. We did not

quite like her, but we respected her and I suspect she understood children

better than they understood themselves.

I went to Miss Howe's School until I was ten. It soon moved into Studio House on the corner of Summer and

Chestnut Streets. I

remember with joy being introduced to Greek myths by

Miss Howe's sister, Mrs. Winchester, pretty and sweet, whom we all adored. Also I found excitement in using compass and

ruler with which we constructed various geometric figures on paper, and much

happiness in using paint brush and water colors. We sang a lot and often, loudly bellowing, "Men

of Harlech in the hollow," and occasionally we

were allowed

to sing some amusing jingle which ended in a near riot.

I remember kindergarten most clearly - the well framed butterflies and moths hanging on the wall, one a

huge Polyphemus moth with the great "eyes" on his lower wings. We learned to make butter in small

churns, to set a miniature table with miniature plates, forks, knives, spoons, fruits, meats and vegetables while

Fraulein Liebert tried to teach us their names in

German. We modelled

objects from cool smooth clay kept in

a large jar in the supply closet. We

made strings of colored beads and wove reins of colored wools. I loved it all.

I think Theodore had to be disciplined more often than any other child. I

remember one day he was very naughty and Miss Howe, in desperation, locked him

in the supply closet. After a long

silence she went to let him out and

found a lighted candle on the shelf and a grinning happy boy busily sticking

the colored beads all through the clay

in the great jar. He was then sent

home. I rose in wrath at this punishment and marched home with him. Ideas of discipline change with each

generation. In Father's, it was the

dunce cap and

switch; in ours, the closet or bed. I am sure we were rather an unruly pair- Although I never

remember being locked in a closet, I remember Theodore was several times. I well remember when he kicked a panel out of

the nursery closet door, crawling through the opening with a triumphant

smile on his face.

I have a photograph which Betty Coggin sent to me a few years ago of the members of

Miss Howe's School while it was still in Hamilton Hall. There were nineteen of us. The girls all are wearing some kind of hat -

flat sailor hats, scoop sailor hats, ruffled hats, hats trimmed with high

stiff bows, chiefly according to age. Totty Benson is wearing a ruffled bonnet which I vaguely

remember as red trimmed with white. The

boys are all wearing round cloth sailor caps or snug fitting little caps. It was as unthinkable to go to school or even play out of

doors without a hat as it was not to wear long-legged underwear and high boots in

the winter months. Both boys and girls

wore long black stockings. In the photograph

my sailor hat is on the back of my head probably held on by an

elastic under my chin. I seem to be the most disheveled of them

all. The photograph was taken on the

steps of Hamilton Hall. Outside was a

wide strip of asphalt instead of brick for a sidewalk. This made a splendid place to play hopscotch

or jump rope. A horse chestnut tree

shaded this area and added to our joy in the Fall when

the splitting burs fell to reveal the lovely smooth rich brown nuts

within. We collected these and sometimes

made chains by stringing them on stout thread.

When I think of the chestnuts the image of Mr. Wentworth comes to mind. He was the janitor and lived in rooms on the

ground floor. He was darker than the chestnuts with very white teeth, and he

was kindly and friendly.

Hamilton Hall was built in 1806 and named, of course, for Alexander Hamilton, who,

in spite of careless modern explanation, never danced there. The architect-builder was Samuel McIntire

whose designs

and carvings so enriched Salem's architecture in that period. It remains one of

the most treasured buildings in Salem. I

do not wish

to try to describe it here except to say that it and the South Church which stood directly across the

street, but which burned down in 1903, made

Chestnut Street with its great merchant houses one of the most distinguished

streets in America. How marvelous it

would have been if the church could

have been rebuilt exactly as it had been, for it was probably the most

beautiful of all the Federal New England wooden churches.

We went to dancing school in Hamilton Hall for years because dancing school seemed to be more of a

party than a class. The girls wore wide hair ribbons and wider sashes to match,

and patent leather slippers with one strap; the boys, patent leather pumps with

flat bows, Eton collars, broad ties and tight, above-the-knee-length dark blue

trousers and coats to match. We felt

very handsome. Miss Pitman,

gray-haired, plump but exceedingly light of foot, in her ankle-length

light blue accordion pleated silk skirt, carrying a fan, made

it all seem quite festive. She wore a suspicion of rouge on her cheeks which in those

days seemed almost naughty to us. The

last half-hour was usually spent dancing one of the two square dances we

learned: the Portland Fancy and the

Lancers - or often we danced a German, and always the finish was a wonderful

grand march. When I see the Frug or the Watusi today my heart

goes back to the little boys - later the big boys - gravely placing a hand on

their tummies and making a deep bow before the little girls - later the big girls -of

their choice. The floor of the old hall,

supported by chains, would begin to heave ever so gently when we began to

dance the polka or the schottische, and the three great gilt mirrors (still there)

would reflect the kaleidoscope of gay colors of dresses, hair ribbons and sashes.

I loved Hamilton Hall. It stood diagonally across from our house in the same

block with nothing between except our garden, the Coggins' woodshed and

another small garden. Often at night I

could see the shadows of dancing couples flit by the lighted Palladian windows and I could

hear the music drifting across the space between.

The shed roof belonging to the Coggins, which I just mentioned, I speak of rather shamedly. The Coggins, Mrs. Raynor Wellington's

family, were lovely people, kindly and patient - patient because we and our friends

loved nothing better than to climb the various slopes of the various roofs of their

ell and woodshed which stood directly at the foot of our garden behind our little

"barn." As we

grew older, we grew bolder, and I remember with shame one day helping some older boys carry

good sized stones up to the shed roof to throw down at the Coggins'

garbage pail while Billy shook his fist and swore at us. Dear Billy - who as a little boy, not quite

old enough to go to kindergarten, stood on the sidewalk outside his house to greet me and to say

he wished he could go too; and who a few months after he had graduated from

Harvard in 1916 was carried to his death in a Boston trolley car which plunged

through an opened drawbridge near the South Station in Boston.

Fires in Salem were often serious.

I can feel my heart pound at the memory of the first blast of the

bellowing fire alarm which Often woke me at night to make me lie rigid while I

counted the number of blasts from its cavernous source. Any number in the fifties or a second alarm

would bring me tumbling out of bed to see if I could see any flames. Too often the lurid light of a night fire would be visible, and

then with a dry mouth and a pounding heart, I could not sleep again until I heard

the two blasts of the all-out signal. I

experienced too many serious fires ever to have peace of mind when there was

one in Salem, and perhaps I was not so foolish after all because most of Salem did

finally burn down in 1914 when Mother, Rebecca and I were abroad. The two I remember with real fear were when the South

Church burned and when Mechanics Hall, our only theatre, hurled firebrands in a strong

wind over our little section of the city.

The South Church was being prepared for its one hundredth birthday about

Christmastime in 1903.*

Members of the parish had been decorating it all day. Father, as was his custom, took Siggy, his black cocker spaniel, to walk before supper. This time I asked to go with him. As we passed the South Church, only a block

away opposite

Hamilton Hall, we saw through the basement windows a mass of firey, roaring flames.

There seemed to be no one else in the neighborhood, yet someone else had

seen the flames because just then the fearful fire alarm blew, and it was our

own box, number fifty-six. In two or

three minutes swinging around the corner at the head of Chestnut Street, a

quarter of a mile away, came the fire engine. We could see the

reflected glow on the billowing steam and hear the drumming hoofbeats

of the galloping horses. I had seen this

sight many times before and I think it is the greatest sight I shall ever see -

the gleaming engine, with sparks showering from it, drawn by three great black

horses abreast, each with four white feet and a white nose, plunging right down

the middle of the beautiful wide street arched with towering elms. I always felt exultant, as if I were watching

St. George slay the dragon. This was

"our" engine, "our" horses from "our" engine

house. I had even been in

"our" fire station at the time of a fire alarm and had watched

"our" horses trot out from their stalls, when the gates flew open, to take

their

![]() I may be wrong about

its centennial. The clipping says it was

built in 1805.

I may be wrong about

its centennial. The clipping says it was

built in 1805.

places under the harnesses which then dropped on

their backs. I had watched the firemen

slide down the brass pole from above,.snatch

up their

rubber coats and hats, snap one or two buckles on the harnesses and jump on the fire engine even then

leaving the station. I am sure that anyone who has seen the run of a horse-drawn

fire engine thinks of it as the most dramatic sight he will ever see.

This time a second alarm followed by a

general alarm sounded almost immediately.

The spire of the church was one hundred and sixty-five feet tall. If it fell outward across the street it would

fall across Hamilton

Hall. If it fell to either side it would

fall across houses. The only way to prevent a terrible conflagration

was to make it fall within the

church.

Father and I went home to warn the household

of the great danger. Apart from packing

up some silver and personal papers there seemed little one could do but wait. Before very long we could see from our third story windows that the spire was

beginning to burn. The heat became so

intense that we closed the windows. I

remember watching the flames as long as I could bear it, finally getting a little

history book (I was only nine) to read aloud to Mother about Christopher Columbus. I really hated Christopher Columbus because

it seemed as if everyone wished to read about him to me, but this time

he came to my rescue. Finally we went

back to watch the spire fall. The hoses

had been played on the fire in such a way that, like a great tree, the spire fell within the ruins of the church.

Sparks flew up and out all over the neighborhood, but other hoses were

ready, and neighboring roofs had been wet.

The excitement was over, the beautiful old church was gone and Salem was

so much the poorer.

I wish I could note that the parishioners rebuilt the church in the old

design. Despite petitions from many

leading citizens, they refused, fearful of another fire.

They built a suburban-looking stone church, an anachronism in that location . Mr. Francis Lee, a great wag and a friend of my parents,

who lived in a beautiful Chestnut Street house (later bought by Frank Benson,

the artist), remarked that it looked as if one of the Newtons

had flown over Salem and laid a church.

Years later the Chestnut Street Associates bought the church,

pulled it down and turned the site into a little park.

Only last Thursday, Rosie Putnam took me to a lecture in Hamilton Hall

and to lunch there. She told me that

there was great pressure to turn the park into a ball field. If only a Mr. Rockefeller could rebuild the

church and help the Chestnut Street Associates maintain this handsome street!

Whenever I feel discouraged about the

present world (and goodness knows there is enough cause right now) I am apt to remind

myself of the

social make-up of Salem as I remember it.

Anyone who has read Marquand's "Point of

No Return," a satire about the "upper-uppers" and

"middle-uppers" and "lower-uppers" - social distinctions in

old Newburyport - will understand a little of how it was in Salem about

1900. Wealth seemed to have

little to do with social acceptance there.

New wealth was almost a hindrance unless the person or family passed the test

of cultural acceptance. An ornithologist

or traveler or scientist or musician or artist or teacher of broad interests usually was

socially acceptable. Yet there was the

inner core of people - usually descended from old first families - who seemed to decide who

was really acceptable: whose children would be invited to dancing school or children's

parties; who would be invited to join one of the three "sewing

societies;"* who would be invited to the three annual "Informals"

and to the two very formal "Assemblies," held in Hamilton Hall. I can think of three or four families in

really straightened circumstances, who participated in all these things. Of course there were fringe families

sometimes included, sometimes not. There

were families whose children were accepted but the parents were not. The area of the city in which they lived had a

little to do with it, those in North or South Salem usually without the

pale because of being comparative new comers, not belonging to Old Salem. All this is interesting to think upon.

Where these acceptable people really did fail

was in their relation to the immigrants. Only one

block away from our house were

![]() Their names:

Their names:

The oldest and most venerable to which Mother belonged: "The

Cheerful Workers."

The next oldest to which Aunt Rebecca Putnam belonged: "The

Busy Bees."

The younger set belonged to the "Thread & Needles." Daughters

usually were elected to

their mothers' club.

three streets where I never dreamed of

going. Creek Street, which was mockingly

called Greek Street, Gedney Court and High Street. Not many years

before, these streets had been gardens of old houses or narrow ancient lanes,

once charmingly quaint

perhaps (Creek Street followed the creek which flowed through my

great-grandfather Cox's garden) but into which the Greeks and Italians, who worked

in the

mills, overflowed. Norman Street where

we did go and where Cousin Sarah Smith lived and where the large Cox mansion

was, in which the numerous Coxes, including my grandmother, were born and grew up, was

even in my childhood being turned into a slum neighborhood. These slums have gone,

having been cleared for business or parking areas, and all the original

quaintness and greenness has gone also.

As far as I know, few people did anything

for these mill people until Aunt Rebecca Putnam in the teens and twenties

started a small settlement house in the old high school building across from our house

on Broad Street. Mother was interested

in working girls -largely shop girls - and for years worked hard for the Women's Bureau,