written by Charlotte Chapin Crowninshield, b.1868

d.1967

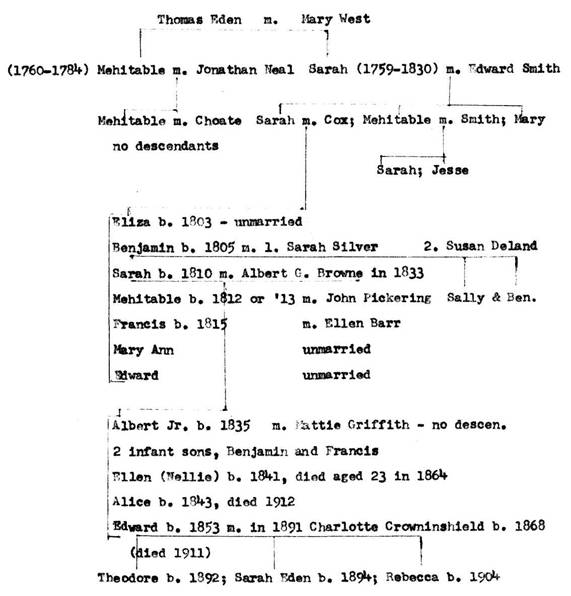

with an introduction from her daughter Sarah Eden Browne

The Brownes

and the Coxes

1952 – 1960

During my short summer visits

with Mother in her little house at Chocorua, New

Hampshire, I used to ask her questions about our family history. As soon as was

possible I would write down all that I could remember of our conversations, and

because I did so I think I captured the spontaneous manner with which it was

told. It was not until we were well along in Crowninshield

history that I began to take notes openly.

Mother has been patient in

answering endless questions correcting- me when my memory became hazy. Carey

has spent valuable hours going over this manuscript, helping to clarify points

which to him were not clear but which to a person more familiar with the family

history might not seem so obscure.

So this is the product of all

three of us for our family with our love.

Sarah Eden Chamberlin

December, 1962.

This I wish

you to know, Sally. You remember the house (pulled down in 1955 for parking lot of Full's

funeral establishment, which was Dr. Phippen's

handsome house!) by the Salem Common where Eleanor Lawson used to live - the

one behind Dr. Phippen's? That house, a lovely old

house, was brought from Kittery,

Maine, by boat by your great-great grandfather, Joseph Vincent. He was

the Vincent who owned the ropewalk and

who helped supply the rigging for the "Essex". He had a

powerful personality. It was said that you could hear him sneeze even across

the Common.

His

daughter, Lydia, married James Browne and they became the parents of Vincent,

Albert Gallatin, George, John White, Charles, and Lydia. The Vincent forebear

had been a Florentine - ropewalk

Vincent's father.

James

Browne was a friend of Dr. Bentley - both ardent Jeffersonian democrats in

Federalist Salem. Dr. Bentley it was who christened James' and Lydia's second

son, Albert Gallatin Browne,

much to the disapproval of most Salem people, for Albert Gallatin was at that

time Jefferson's Secretary of the Treasury, and Jefferson was not popular in uptown Salem.

Those Browne boys were a vigorous lot. Charles became a wealthy chemist in Boston and lived on the water side

of Beacon Street. He was one of the large benefactors of the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology. You remember his daughter, Cousin Rebecca Greene, do you not?

She was a rare and lovely person. I used to take you to her house - she

inherited her father's house - when you were a little girl. She had no

children, as you know. Her husband was a somewhat retiring New Bedford lawyer, so

we rarely saw him. Your father used to

call him "Invisible Greene".

But Cousin Rebecca was a warm, outgoing person whom we all loved, Lewis Gannett's father had been in love with her at

one time.

George went to New York and became a Wall Street

banker. He became wealthy also. His son, the father of Belmore

and Ralph Browne, was also a George and went out to Tacoma, Washington. A daughter, Georgianna,

married the brother of John LaFarge. Whatever happened to that family, I do not

know, but Evelyn Browne perhaps could tell us.

Albert Gallatin Browne, of course, you know all about

— your grandfather.

Vincent — Uncle Vince — became the founder and

treasurer of the Salem five Cents Savings Bank "to encourage the spirit of

thrift among children and adults".

He married a Hodges from North Andover. He never had any children. Some lovely old things left to him by his

Bother went to the Kittredge family, consequently,

and never came back to the Brownes.

John White Browne was Charles Sumner's classmate and

close friend at Harvard. He became a law

partner of Governor Andrew but he died in the late 1850's while still fairly

young, before the Civil War. You have a

memorial monograph of him written by your Uncle Albert. (It is interesting to

know that Albert G. Browne, Jr., became Governor Andrew's military secretary

during the Civil War. Robert F. Bradford, when he was the governor's secretary,

and later as governor himself, showed us A. G. B.'s

hand-written state records kept in the Massachusetts Governor's office. S. E. C.)

John White Browne married Martha Lincoln of Hingham

where he lived after his marriage. Their

only daughter, Laura, was some-what of a recluse and remained unmarried.

I have a photograph somewhere of the old chair which

the original Florentine Vincent brought to this country. It finally went to California, taken there by

one of the Brownes, I think.

I told you yesterday that the Florentine chair was

owned by one of the Brownes. I have been thinking about that and I am sure

I was wrong. I am sure now that it was

inherited by a Vincent son and then by his daughter who married a Narbonne — a French Huguenot family. Old Mrs. Narbonne

had the chair. It was her grandson who

took it to California. Matthew Vincent

was the name of the Florentine. His sons were Joseph and Matthew. Joseph married a Hart for his first

wife. His second wife was Lydia Nowell. It was said

that Lydia could not make up her mind.

Joseph showed her his watch one day and told her he would be back in

exactly one hour for her answer. That worked, for she married him and they

became the parents of Lydia Vincent, your great-grandmother.

Besides five boys, James and Lydia had one

daughter. She was Lydia, also, and

became Mrs. Gardner of West Roxbury. She

was an ardent Unitarian. It is

interesting to know that when I became engaged to your father she told me that

the Roxbury church was so undecided about whether it wished to call my father

or Mr. DeNormandie that each was invited to fill the

pulpit for two or three months. It was this invitation and another letter from

the Belmont church, calling my father to that pastorate, which arrived in the

mail the day after he died.

I do not know where the Brownes

came from but I have supposed it to be London.

You are wrong about Peterborough; it was the Coxes

who came from there,

Elder Browne was the original Browne to come to this

country, in 1636. The Tory Brownes are an entirely different family, I think; at any

rate at the time of the Revolution they were, and very well-to-do at that. It was that family which built a house on

Folly Hill — Browne's Folly — so-called because they found there was no water

to be had once the house was built. That

family went to Halifax at the outbreak of the Revolution. It was also that family which founded the

Harvard scholarship for any boy by the name of Browne from Salem, and, if none,

for a deserving boy of any name. It was this scholarship which George Browne in

Tacoma tried to get for his son, bat it was then being used by Manuel and

Sidney Fenollosa, the father and uncle of the present

Manual and Sidney. The Ernest Fenollosa, who became

an authority on Oriental art, was a half-uncle to these boys. They needed aid more than the Tacoma Brownes. Your father

went to see Dean Briggs about it and learned this than.

"Elder" John Browne may be the same as

"Lawyer" John Browne who had returned to England in 1632, saying that

he "preferred the prayers of the Church of England to hearing Parson

Skelton pray and preach". (Quoted from Samuel Eliot

Morison.) At any rate Elder John

Browne settled on what is now Elm Street next to Henry Bartholomew. His son, James, married Hannah Bartholomew

and went to live in what is now Peabody, near two ponds, later known as

Browne's Pond and Bartholomew Pond. His son,

James, married Elizabeth Pickering, so the original John Pickering is your

ancestor also.

Very early in the sixteen hundreds the Brownes were ship-owners and carried on a coastwise trade

with Virginia and Maryland. They also owned plantations or land in

Maryland. The son of Elder John Browne

was murdered in Maryland by a negro. No, I don't think that they traded in slaves,

but I think that they traded in rum and molasses. They were an adventurous, independent line of

men.

James Browne, year great-grandfather, was a

ship-chandler and sea-captain. He may

have had an interest in the Vincent ropewalk, but I am sure the Brownes ware ship-chandlers themselves, supplying many

articles besides rope.

Your grandfather's business was in Boston with the

firm of Whitin, Browne and Wheelwright. They were ship-chandlers and had their office

on the old milldam somewhere in the vicinity of where Beacon Street and Charles

Street now meet. I do not know where it

was exactly and have always meant to look that up. As a younger man he had been in business in

Salem and Uncle Frank Cox, as a teenager, had been in his employ, but when

Boston became the shipping center he moved his business there.

Your grandfather was impulsive and not always

practical. It was said in the family

that he gave away to someone in need some new shirts, which his wife had just

laboriously made. During the Civil War,

at great sacrifice, he became an agent of the United States Treasury, valuing

contraband and properties which fell into the hands of the Union. There had been no provision by Congress to

pay these civilian agents and Congress never got around to pro-viding pay for

them even after the war was over. So

Grandfather, having resigned from his firm to take this arduous business, came

back quite depleted financially.

There were other sorrows connected with the Civil

War. His headquarters were established

in Beaufort, S. C. He hated to be

separated from his family and finally induced his wife to bring the two girls,

Nellie and Alice, and your father — then a little boy about ten years old — to

Beaufort to be there with him. Nellie

was an unusually lovely young person, beloved by all the family and her friends. She became engaged to Colonel Lewis Weld

whose family were Philadelphians and whom I later came

to know. (Incidentally, Lewis Weld's cousin was Lily Van Rensselaer, who

married Mr. Burd-Grubb, one of our ministers to

Spain. Her young cousins affectionately

called her, "Mrs. Canary Seed".)

Lewis Weld, as a young lawyer, had gone out to Colorado, becoming the

first governor, or, I suppose, commissioner, of that territory. He organized the regiment of which he became

colonel. Nellie had already known some

of the Weld family through her Cambridge schoolmate, Sally Howard (later Mrs.

Hayward). Plans ware made for the

wedding, but Nellie, who had been nursing in a military hospital, came down

with "southern fever" — I suppose typhoid fever — and died in June,

1864 when she was twenty-three years old.

Lewis died of wounds received at Petersburg six months later. It was he who designed the stone at Nellie's

grave, in Harmony Grove, Salem.

The family — both families — never really recovered

from this shock and it left an indelible scar upon your father who was a

sensitive, lonely little boy through those tragic years. It was a sad and ill family which finally

returned to Salem. Grandfather never

recovered from malaria contracted at that time, although he lived until

1885. Grandfather and Grandmother Browne

died within two weeks of each other, Grandmother having been an invalid in her

room for six or seven years.

Your wedding-dress, made over from my wedding-dress,

was of the material originally brought in a Salem sailing-ship from China, which

was to have been for Aunt Nellie's wedding-dress. It was laid away again until I was engaged to

your father many years after. I was deeply moved when he gave it to me to be

mine.

I never knew your grandmother but I was repeatedly

told that she was a rare, sweet woman, eager to help others and patiently

bearing her own burdens which were many.

She had lost two baby boys during those second summers, fateful for many

babies in those days. You can read the

sweet strength of her character by looking at the old photographs.

I have spent mach time when I had physical ability, in

looking up the first Brownes in this country. I used Felt's Annals, Samuel Eliot Morison's

"Maritime History of New England", papers and documents at the Essex

Institute and the Boston Public Library.

I have various notes and sketches to put together some day to hand on to

you children. There is a record also in

the old Browne Bible, brought to this country in 1628, carefully compiled by

Benjamin Browne, a cousin of your grandfather, who died in 1862.

You asked how Lawyer Browne and Elder Browne could be

the same person. Your father never

thought they were, but Morison thinks so. Lawyer Browne came over to this

country with his brother William, representing the English company which had

financed the colony at Salem. Lawyer

Browne was one of two brothers sent back in 1632 by Endicott as

"undesirable" because he was a Church of Englander. He must have changed his interest and

sympathies to have come back again in 1636 to become Elder John Browne. Morison thinks he had to pretend loyalty to

the Church of England while representing English interests. However that may be, all this is

Massachusetts history and can be had from books.

I came across an old map of Salem in its early days —

1650. This showed that the harbor came in vary close to the foot of what you

knew as Creek Street, where ships used to be built. It also came almost up to old Elm

Street. The map shows John Browne's

house next to Henry Bartholomew's house there, with the land sloping down

toward their wharfage and the high ground of the Old

Point Burying Ground — now the Charter Street Burying Ground — jutting out into

the water.

1st generation.

John Browne was repeatedly chosen as Elder. He was loath to assume this responsibility

because he was a merchant and a mariner trading with Maryland and

Virginia. He was received as an

in-habitant of Salem in 1636.

2nd generation.

His son, James, was born in 1640 and married his

neighbor, Hannah Bartholomew. He was

murdered by a negro in Maryland.

3rd generation.

Their son, James, was born in 1675. He married Elisabeth Pickering, the original

John Pickering's granddaughter. They

went to live in what is now Peabody near the two ponds named Browne's and

Bartholomew Ponds.

4th generation.

Their son, William, born in 1710, was captured by the

French and was drowned while trying to escape.

He had married Mary Frost.

5th generation.

Their son, William, was born in 1735 and died in

1812. He married Mercy White, who died

in 1785. This is where John White Browne

acquired his name.

6th generation.

Their son, James, was born in 1759 and died in

1827. He married Lydia Vincent and

became your great-grandfather.

7th generation.

His son, Albert Gallatin, was born in 1805 and died in

1885. He married Sarah Eden Cox (1810-1885).

8th generation.

Your father, Edward Cox Browne, was the eighth

generation. He was born in 1853 and died in 1911. He married me! — Charlotte

Chapin Crowninshield, born in 1868.

Theodore and Ted make the ninth and tenth generations,

and Ted's sons the eleventh.

Before we go on about the Brownes,

I should like to mention Henry Bartholomew, who settled next to John Browne on

what was later Elm Street. Henry

Bartholomew came to Salem in 1635, with five brothers, from Ipswich,

England. Henry was made a

"freeman" in 1637 and became the clerk of court. He was fearless and independent and became an

important man in the community. His

interest was in the local mill. It was

his daughter, Hannah, who married Elder John Browne's son.

Your great-grandfather, James Browne, married

twice. He had two daughters by his first

marriage, Nancy who never married, and Elizabeth (Aunt Betsey she was called)

who married a West from Haverhill. Her

daughter, Sarah, married a Palfrey, cane to Boston to live and went to James

Freeman Clarke's church. When a young man James Freeman Clarke lived with them as a boarder.

James Browne married Lydia Vincent for his second wife

and, as I have already told you, had five sons and one daughter. Vincent was

the oldest (Uncle Vince), then Albert, George, John, Charles, and Lydia. George was Belmore

Browne's grandfather, all of which means so much more to us after this winter's

lovely friendship with Belmore and Agnes.

The James Brownes want to

Dr. Bentley's church, which was on the corner of Essex and Bentley

Streets. The golden rooster weathervane

is now all that remains of that church and is now, or was, on the Bentley

School.

In those days Salem was divided politically. All downtown Salem was Democrat — I think the

term was used then — and all uptown was Federalist. There were no half-ways about the division,

just as a generation or two later Salem was divided into the anti-slavery

group, "Antislaveryists", and

Copperheads. Feelings ran high at both

periods. Dr. Bentley was an ardent

Democrat, as were most of his parishioners.

I know that you know about his christening your grandfather "Albert

Gallatin" much to the surprise of many people and without the

foreknowledge of the parents of the new baby, who had asked Dr. Bentley to name

him. However, the parents heartily

approved.

Bentley Street was, of course, named for Dr.

Bentley. Sometime you should read his

old diary to catch the spirit of those times.

The Brownes lived nearby. I remember your father showing me a brick

house where Mercy White was born, James's mother.

As I said, Salem was divided in those days, as it

always has been, in one way or another.

The names, "Hamilton Hall" and "Federal Street",

suggest the leanings of the people in that part of the town. Incidentally the hymn tune, "Federal

Street", had nothing to do with Federal leanings. General Oliver, who wrote it, wished to name

it for his wife, whose name had been "Cook". However, she insisted on

the more formal name, "Federal Street", where they lived at the time.

A brother of James Browne was Benjamin and his son was

a "chemist", Dr. Benjamin Browne.

He really held some sort of a degree and had a chemist shop where

experiments were carried on and where drugs were dispensed. When he was a boy of seventeen or so, he had

been impressed into the British navy and finally was thrown into Dartmoor Prison. Now

I don't remember whether he was exchanged or whether he escaped, bat later he

returned to Salem and married into the Bott family,

whose house was on Essex Street at the end of Hamilton Street, and whose land

ran along Bott's Court. Nathaniel Hawthorne was then

living in "the house on the marsh", on what is now Chestnut Street,

the house in which Rebecca Pickering Bradley now lives at the other end of the

lane. Hawthorne used to elude his

unwanted visitors by escaping up the court to Dr. Benjamin Browne's house to

talk to his old friend. From these

conversations grew Hawthorne's story, "The Prisoner of Dartmoor". I have always thought that was interesting.

By the time your grandfather, Albert Gallatin Browne,

married in 1833, Salem was again divided, this time into Antislaveryists

and Copperheads, as I have said. The

Coxes were quite divided in their own family.

Aunt Eliza, Grandmother's oldest sister, was very lively intellectually

though not as well educated as your grandmother, who used to curl herself up in

the wing chair Rebecca Bradford new has in her living-room and study the Virgil

her older brother, Benjamin, later "Uncle Doctor", was studying at

Harvard. She had an inquiring mind and

educated herself well. Aunt Eliza would have been a feminist in our day. She subscribed to William Lloyd Garrison's

paper, "The Liberator", much to the disapproval of her father who was

inclined toward being a Copperhead.

No, Grandfather Cox did not own ships, I think. Perhaps he would have been called a

merchant. I think he supplied ships with

lead, hemp, and the countless things needed in shipbuilding. His house on Morgan Street you remember in

its sad old days, but it had been a handsome large gambrel-roofed house much

like ours at #40 Summer Street. It had a

terraced garden, pretty with fruit trees, sloping down to the creek where his

skiffs were tied. I think that his supplies

came and went in those skiffs. He must

have had some sort of warehouse but I have never thought of that.

Grandfather Cox was very well-to-do. He made his wealth through real estate

also. He owned many properties in Salem.

The house at #2 Broad Street, next to ours, he brought from upper Summer Street

near Essex Street. Its end, like some

Salem houses, faced the street.

Grandfather saw that it would fit the piece of land on Broad Street and

had it moved there. It fitted into place

like the piece of a picture puzzle. Your

father, I remember, said that the house belonged to someone by the name of

West. It just occurred to me that since

Thomas Eden's wife was Mary West (George and Arthur West were descended from

that West family) this house might have been some Eden property coming down

through the female line to the Coxes. I

have never thought of that before. I did

come across one time the notice of the death of a George Eden West born in

1825, who died in Worcester an old man.

Grandfather Cox had a restless brood. Aunt Eliza and your grandmother became

Unitarians. "Uncle Doctor"

also became a Unitarian and always went to the North Church. Uncle Frank became an Episcopalian when he

married Ellen Barr. He went to St.

Peter's Church which was rather high church, and I, who was very fond of him,

sometimes want with him. Aunt Hitty (Mehitable) Pickering, of

course, was Unitarian like all the Pickerings. It is a wonder they all were so close and

devoted to one another with such varied interests in a day of rapidly changing thought. There were tremendous changes then just as

there have been recently.

Grandmother and Aunt Eliza went to the Barton Square

Church. Grandfather Browne joined Grandmother there when they were married in

1833. They began to go to the North

Church when Mr. Willson came in 1853. Mr. Willson was a

member of the Legislature and a great friend of Horace Mann. They fought long and hard for free books for

school children. He was always greatly

interested in social reform.

Cousin Sarah Eden Smith, who was born in 1824, an own

cousin of your grandmother, was the only one of all that family to remain a

Congregationalist. She attended the Old

South Church on Chestnut Street until she died.

Thomas Eden, so they said, was associated with

"King" Hooper of Marblehead.

"King" Hooper built in Danvers what was later called "the

Lindens" about the same tine that Thomas Eden built in 1762 our house on

Summer Street. The staircases in those

two houses are identical. The Lindens, I

think, was taken down piece by piece and moved to Washington, D. C, a few years ago. It

had been the headquarters of the British General Gage for a time during the

Revolution. "King" Hooper

lived in a good deal of style, but in spite of his airs was a very generous

man.

Thorns Eden, before he built #40 Summer Street, lived

in the old house, still standing, opposite the cemetery further up the

hill. This was the house queer Uncle

Edward Cox, for whom your father was named, owned but he never lived

there. Your father as a boy was annoyed

that he had been named for that particular uncle.

You know, of course, the story of the christening of

our house — how Thomas Eden broke a bottle of champagne over its ridge-pole

with the words, "To the House of Mary and the Garden of Eden". The rafters and ridge-pole are shaped like

inverted knees and keel of a ship for it and many similar houses were built by

ship carpenters. In a fireplace in one

of the front bedrooms is a fireback cast at the

historic Saugus ironworks, representing Adam and Eve, the serpent and the apple

tree in the Garden of Eden.

You asked if the staircase was of a later date, as

David Barnes said it must have been. A

certain refinement of background was transferred frost England to the workmen

in this country, and English plans were carefully studied and adapted to

American use. I am sure if the staircase

were of a later date I should have heard of it, David Barnes' theory

notwithstanding,

To Thomas Eden was issued the first certificate of the

Salem Marine Society, the membership of which was limited to captains who had

rounded the Horn. Theodore owns that

certificate. The Society exists today

and is limited to one hundred members, now all descendants of old

sea-captains. I had hoped that Theodore

would be interested enough to be a member.

Thomas Eden died in 1768 when he was only forty-two,

so he lived in his new house only six years.

He married Mary West and had two daughters, Mehitable

and Sarah. Mehitable

married Jonathan Neal. Her daughter, Mehitable, married a Choate, I believe. Jonathan Neal's

second wife became the grandmother of Mrs. Robert Rantoul. That is where Neal Rantoul gets his name.

Sarah Eden married Captain Edward Smith and inherited

the Eden house. She died there the day

President Jackson case to Salem, making his formal entry through South Fields,

the country which became Lafayette Street.

Cousin Sarah Eden Smith, her granddaughter, remembered this old lady

because she and her mother lived with her in the Eden house for a few years

when Cousin Sarah was a tiny girl.

Cousin Sarah's father, Commodore Jesse Smith, was lost in the ship

"Hornet" which foundered in a Gulf of Mexico hurricane. Jesse Smith was no relation to his

father-in-law. When the grandmother died, the widow of Jesse Smith and her

little daughter, Cousin Sarah, went to live in the little house on Norman

Street where you remember her as a very old lady. At that time your grandmother, Sarah Eden Cox

Browne, came to live in the Eden house and remained there all her married life.

But I am getting ahead of my story. Sarah Eden and Captain Edward Smith had three

daughters: Sarah, Mehitable and Mary. Sarah, your great-grandmother, whose portrait

and shawl you have, married Benjamin Cox and lived in the Cox house on Norman

Street which I have already described. Mehitable married Jesse Smith, and Mary remained unmarried,

spending her life with either the Coxes or Smiths after her mother's death.

Sarah Smith and Benjamin Cox had seven children:

Benjamin, the beloved physician of Essex County, whose children were Sally and

Ben; Eliza (unmarried); Sarah, who married Albert G. Browne (your grandmother);

Mehitable, who married John Pickering; Francis, who

married Ellen Barr whose portrait you have; Mary Ann (unmarried); and Edward

(unmarried).

"Uncle Doctor", so-called,

married for his first wife Sarah Silver. There were no children by that

marriage and he was a widower for several years. He then married Sarah Deland, niece of his

first wife and the mother of Sally and Ben.

After his second marriage he lived in the house on Essex Street which is

now the Essex Institute.

But to go back, Cousin Sarah Eden Smith's father,

Jesse Smith, commodore in the navy, was lost with his ship the

"Hornet" and all the crew in the Gulf of Mexico in 1830. He was commander of the ship. His father had been a member of General

Washington's body-guard. His son, Jesse,

was a midshipman in the navy. He died of

African fever off the coast of Africa when very young. Theodore has the portrait of Jesse, the son.

I forgot to say that Thomas Eden's daughter, Sarah,

who married Captain Edward Smith, was left a widow quite early, for her husband

was also lost at sea. It was said that

she sat in the window of her father's house watching for him to come home, for

many years. So Cousin Sarah lost her

grandfather, her father and her brother all at sea. Your great-great grandfather Cox was also

lost on a voyage, as you can learn by studying the gravestones at Harmony

Grove:

"Benjamin Cox 1733-1778 Died

at Martinique, aged 45."

I am glad I knew Cousin Sarah. She used to tell me many interesting

things. She seemed fond of me. She left me the Pembroke table and the lustre ware tea set.

She would give me tea at that table from the lustre

ware tea set. She knew I admired

them. She was happy that her name was

being carried on in another generation and so she left you the bureau, twin of

the one Rebecca has, both of which had been given by her grandmother (your

great-great grandmother) to her two daughters: Sarah and Mehitable.

The second bureau came to us through the Coxes.

It pleases me to think that they are owned by two sisters once

more. She also left you the six little

teaspoons which you so treasure, one of which she had chewed when a tiny

child. You thought that she also left

you the six Windsor chairs. I do not

think so. They came with the Eden chair

which she left to your father.

I have thought it interesting that these things should

have come back to the house where the old lady had lived who gave them to her

daughters so long ago.

I am sorry that we have to jump around so in telling

you these things, but it is impossible to think of everything without going

back. I want to tell you a little more

about the Coxes and then we can come a little nearer to our own time.

The early Coxes and all the Smiths were sea-captains,

but the

Brownes became ship-chandlers quite early, I think. The Cox children — your grandmother's

brothers and sisters — were all so independent that they could not live

together. Aunt Eliza lived in the Summer

Street end of the Eden house. She died

in 1888. The Brownes

went to live in the Broad Street side in 1835, for what we knew as 40 Summer

Street and 1 Broad Street has been first a single house, than a double house,

and so on right down to the present.

Aunt Mary Ann, who died in '88, lived where Aunt Rebecca Putnam lives at

34 Summer Street, and Uncle Edward, after his parents' death, lived all alone

in the Cox homestead on Norman Street.

He was somewhat eccentric, somewhat of a recluse. Your father was first named

"Theodore" but after about six weeks your grandmother, who had a soft

heart, changed the name to "Edward", realizing that she had left her

brother Edward out. One little boy had

been called ""Benjie" for her brother,

Benjamin, and one had been named "Frankie" for her brother,

Francis. As a child your father disliked

his name because he considered Uncle Edward odd, but Uncle Edward loved us and

the family really all loved him.

Now when Aunt Eliza died the Brownes

bought 40 Summer street which had been the part of the

house belonging to Cox and Pickering heirs.

The large elm trees in front of our house had been little seedlings

which Grandmother Browne brought in her handkerchief from the Storey garden on

Winter Street. She started them in the

garden first, later transplanting them.

Did I say that Hannah Storey had been one of Grandmother's bridesmaids

and that Caleb Foote was Grandfather's best man?

You say that you remember Uncle Edward as an old bent

white-haired man. I am sure that you

could not have because he died long before Uncle Frank, who died in 1898 on the

night of the great storm when the steamship "Portland" went down.

Aunt Mary Ann at one time had been engaged to Dr.

Haddock, the father of the Dr. Haddock who lived next door to the Chamberlins in Beverly on Lothrop

Street. Cousin Sarah Smith's mother

(Aunt Hitty) said, "I don't believe it because

aha has not brought home a sample of him for her mother to see". Aunt Mary Ann always brought home samples for

her mother's decision. As a matter of

fact she decided not to leave her mother and did not marry. Your father was at Price's Drug Store — then

called "Apothecary Shop" — buying medicines for Aunt Mary Ann the

night before she died. He told the clerk

the name of the patient for whom the order was.

A stranger turned and said, "For whom did yon say? Miss Mary Ann Cox?" It was Dr. Haddock. Price's Drug Store long years before had been

Dr. Browne's Apothecary Shop. The Price

brothers were his apprentices.

People loved Uncle Doctor, Mrs. George Emerton, who had been his patient, told me. He had his office in the Choate house, next

to the Cox house on Norman Street, where he lived during his first

marriage. As I said, he married Susan

Silver Deland for his second wife. Their

children ware Benjamin and Sally who was just my age. Uncle Doctor had a very large practice all

over Essex County. Family legend said

that when he was a young man, during a smallpox epidemic in the area, he was

the only doctor who would venture down to the "Pest House" on Salem

Neck outside the town gates to care for the sick people there.

Your father used to tell this amusing story which I

have remembered. When William, Uncle

Doctor's coachman, was driving him in the vicinity of North Reading they came

to a crossroad. William, very puzzled, asked, Dr. Cox,

what is that sign "No Reading" doing way oat here?"

When the Deland parents died Uncle Doctor bought their

house on Essex Street and lived there with his wife and two children until he

died. That house is the Essex Institute

today. In the early 70's he was fixing

an open fire and struck his head on the marble mantlepiece. This injury led to his death. In the early eighties his widow, Aunt Susan,

and the two children, Sally and Ben, moved to Boston. Sally was a lovely parson — just my age. She died of tuberculosis in Davos Platz, Switzerland, long

years ago in 1902.

There was a passage through from the Cox garden to the

Safford garden and the Cox and Safford children used to play together and were

always intimate friends. The Safford

house is the beautiful Federal style house on Washington Square.

Ben was two years older than Sally. He was a great friend of Neal Rantoul. He came to an early end also. He was worried over some financial troubles

and also he had been unsuccessful in love. He committed suicide only two days

after he had been in our house. His mother was a dominating person — nice, but

no one you could love very much, and I suppose Ben had been nagged by her. Anyway, she was no one to whom he could turn

for help and he had lost his father a good many years before. This was a tremendous sorrow to Uncle Frank

because he had loved Ben dearly and Ben was the only one of the large Cox

family who could carry on the name.

Uncle Frank used to say that when Ned came to spend the night he was

very orderly and good, and when Ben came everything was in a great mess and

turmoil, in spite of which they loved him dearly.

I gave Uncle Doctor's Harvard Medical School diploma

to Harrie because he was the only one in the family

to follow Uncle Doctor's profession in well over one hundred years. I hope he will become just as beloved.

Uncle Frank Cox was five years younger than your

grandmother. In 1840 ha married Ellen Barr whose portrait you have. She died ten years before Uncle Frank. They had no children of their own but their

nieces and nephews became substitutes in their loving hearts and their house

was a rendezvous for the family. Uncle

Frank built the house at 1 Chestnut Street at the time of his marriage and

lived there for nearly half a century, until he died in 1898. You must have memories of your baby visits;

of his cookie jar which he commissioned Julia and Susan, his faithful

housemaids, to keep filled for the new generation.

When Theodore was five Uncle Frank invited us to go

with him to Crawford House for a week or ten days. He said, "Take the boy", and one of

my cherished memories is of the tall stately man walking down the board-walk

with a tiny lad holding on to a finger of a hand reaching down to lead

him. This picture touched other hearts

as well. The cinnamon-brown suit, which

the little boy wore, was a gift from this great-uncle. Though he did not select it, Uncle Frank was

as proud of that suit as if it belonged to his own wardrobe.

Uncle Frank had been president of the Naumkeag Mills, trustee, then president, of the Naumkeag Bank, trustee of the Plummer Farm School, Reader

in St. Peter's Church. He was the only

Episcopalian among his relatives, leaving the South Church Society, at the time

of his marriage, in which he had been brought up.

There is a story that should not be lost about Uncle

Frank's handyman, Hartnett. Every

morning he hosed down the granite steps of Uncle Frank's house, the sidewalk

and gutters. One of the high school boys

loved to tease Hartnett by standing on the hose, sometimes drenching him with

the sudden release of water. He

complained to Uncle Frank, who told Hartnett to identify the boy and he would

do something about it.

"Edintify", said

Hartnett with his brogue, "what's that?"

"Mark him, catch him, and bring him to me",

said Uncle Frank.

One morning Uncle Frank heard a great commotion in the

vestibule. When he opened the front

door, there was Hartnett collaring a boy and soaking him with his hose.

"What on earth are you doing, Hartnett?"

shouted Uncle Frank.

"I'm Edintifying him,

Mr. Cox. I'm Edintifying

him and bringing him to you."

The boy was probably absent from school that day. He never troubled Hartnett again. He grew up to make quite a name for himself.

There is always so much that pops into my head that I

wish to go back to the Brownes. Your father used to tell this story with such

merriment. Your grandfather and his

brother, John White Browne, had gone to Andover to an abolitionist

meeting. Late that night they were

driving home, when Uncle John noticed that they were going in the wrong

direction. "Albert, the moon is on

the wrong side of the buggy. This can't

be the road to Salem." So they knocked at the door of a silent dark house

and finally roused an old man who put his head, covered with a nightcap, out of

the window. "Where are we?"

Grandfather shouted. "In North

Andover", was the reply. "We

can't be", said Grandfather, "We left North Andover hours

ago." "Damn it, young man,

don't you suppose that I knew where I was born and brought up!" And with that he slammed the window shut.

Uncle John White Browne was brilliant. His older brothers helped to put him through

Harvard College. Be became a successful

lawyer. In college he was a classmate

and close friend of Charles Sumner.

Later he was asked to be a candidate for representative in Washington

but he refused to have anything to do with a government which condoned

slavery. All the Browne boys ware strong

anti-slavery backers and became friends of Charles Sumner. Grand-father and John White were in the

underground railway with John Greenleaf Whittier. That is how Grandfather's friendship with him

came about and why Whittier wrote us a note when Theodore was born.

Charles Sumner disappointed his anti-slavery friends

by com-promising — I think by supporting the Fugitive Slave Law. This led to

absolute repudiation of Charles Sumner by the Brownes,

and Uncle John's close friendship with Sumner was completely broken.

Uncle John's life is written up in a little memorial

volume by your uncle, Albert G. Browne, Jr.

It tails all this and much more.

There was some question whether he committed suicide when he fell from a

moving train between Hingham and Boston.

It might have been so because he had withdrawn from all politics to his

home and garden in Hingham. I think he

was one of the uncompromising idealists of this world who either break or are

broken. Your father used to say, when he

was in the City Council in Salem, that he did not wish to be like Uncle John —

uncompromising — that to be effective you sometimes had to choose the leaser of

two evils.

Charles Sumner came to Uncle John's funeral, healing

the open wound by shaking hands with his brothers.

Sooner or later we'll come nearer to your generation

but after all there is no one left but me to tell you of these earlier times,

and there is such to tell. You ask about

your father's schools. Yes, he went to a

dame school ran by Miss Frye at 18 Chestnut Street which is where Rebecca

Bradley now lives. The water used to

flow down from Essex Street during a storm and collect in the cellar, and it

was there the children used to paddle around in tubs, as you say he used to

tall you.

The next school for him was a boys' latin school — Oliver Carlton's,

over the hill on Flint Street. I think

the old brick building is still standing.

Oliver Carlton was a great disciplinarian, using dunce stools and caps

and switches and all the rest. You say you remember your father telling of the

boy who kept tipping back in his chair.

Yes, it was he who cut off the front legs of that boy's chair.

The next school was one run by Mr. Shepard Waters in

the old Devereux house, a large square house on Pleasant Street very near Essex

Street. This was an old Crowninshield house built by Clifford Crowninshield. Later Miss Devereux lived there, an aunt of

James Waters. Mr. James Waters was blind and I used to go there to read to him. At the time that your father was a boy the Footes were being brought up in Salem. Old Caleb Foote was still the editor of the

Salem Gazette. Arthur Foote, his son,

the uncle of Mrs. Cornish and Dr. Henry Wilder Foote, used to play with your

father. Arthur Foote was very bright and

tall for his age. Mr. Waters sometimes

would leave him in charge of the school but he was not equal to the task. The children used to raise cain while Mr. Waters was away and

they would then threaten Arthur not to tell on them. He never did.

For some reason the children called him "Doughnut". Arthur Foote became the musician and

composer. Your father acquired a fairly

good old-fashioned training at this school.

From there he went on to the Institute of Technology,

graduating in 1874. There he made

friends with three brothers known as "Big Dab", "Little

Dab", and "No Dab at All".

One day when your father was crossing Boston Common he saw Big Dab ahead

of him. He ran up to him and slapped him heavily on the shoulder, and then stammered,

"Excuse me, I thought you were my

friend". A complete stranger turned

to face him and said with a good deal of heat, "I hope that your friend is

in good health". Dr. Webster who murdered Dr. Parkman, was these Dabney boys' own grandfather. That was a famous

murder. I think Dr. Webster lived on

Phillips Place in Cambridge because when your Uncle Albert boarded on Phillips

Place, when he was reporter of the courts, he said that the grapevine was still

growing on the fence between there and Dr. Webster's. Dr. Webster had burned some of it to kill the

odor of burning flash.

After Technology your father did some surveying around

Salem and later went to Texas as a construction engineer in bridge building. Shortly his father became an invalid and was

very difficult. Your grandmother had been an invalid for a long time. Aunt Alice could not cope with all this burden so your father came home. From then on he

stayed at home interesting himself in civic affairs. He loved history and had

manual skills; consequently he had hobbies. There was enough money to keep them

comfortable.

Grandfather was a vary impulsive man, feeling

intensely any injustice which he saw done to others and becoming involved in

situations which he considered caused by injustice. This made him an active antislaveryist. I fancy he was not an easy person to get

along with, and, as I said, he was a difficult patient. He was by no means an

unpleasant man but merely erratic. He

was very generous, open-hearted, made life intensely interesting, was always in

touch with significant people but he was exhausting.

Albert Jr. died in June, 1891 before we were

married. His marriage had alienated him

from his family. He married Mattie

Griffith, a Kentucky woman of strong determined character who had freed her

slaves and who was a friend of the literary liberals in New York. Albert was thenceforth under her thumb and

she would have nothing to do with his family in Salem. In 1885 his father and mother died within two

weeks of each other. After their funeral

Mattie went around marking the things she and Albert wanted: books, the John

Brown pike, the Browne family Bible, etc. This hurt deeply. When the packer came, Aunt Alice wanted to

take the problem to law, but your father overrode her wishes and kept the

peace. Albert, who had a good deal of

money, took one-third of the property although he had had no care or

responsibility for his parents. Uncle

Frank talked to me about this and said, "Albert became selfish after he

married that woman".

Albert was brilliant and had had a brilliant career.

He had been devoted to his father and mother earlier. During the war he had

bean Military secretary to Governor Andrew.

His papers, interesting records and all his possessions, except the

Browne Bible, went to his wife. She in

turn left everything to her nieces, who felt that the John Brown pike and the

five shield-back chairs, which Rebecca now owns, should go back to the Brownes. Where all

the other things of family interest are, goodness knows.

Perhaps now is a good time to tell you about your

fiddle-back chairs. The Coxes had six

which went to Uncle Frank. Three came to us, which are now yours, and three

went to the Pickerings, which are now Rebecca

Bradley's. There are some interesting

photographs of the old Cox house on Norman Street, showing many pieces of

furniture which you children now have. The Coxes had taste and the sense not to

discard the lovely old things in order to replace them with heavy Empire or

Victorian pieces as so many people did.

Uncle Frank, who, as you know, lived nearby at the

corner of Summer and Chestnut Streets, was very dear

to me when I came into the family as a young bride. He gave us $300 for silver. I wanted to own a piano above all things and

asked him if he minded my buying a piano with that money instead. Your father added another $300, and that is

the piano I have always loved and which is in Theodore's house in Chocorua. Uncle

Frank died in 1898 on the night the steamship Portland disappeared with all on

board. The storm was so severe that it blew in the French windows of his house.

But to go back to Albert. In the

Sixtieth Anniversary Report there is a good life of him written by his

classmate, Robert Rantoul, of the Harvard class of 1853 — incidentally

President Eliot's class also — the year your father was born. He was only eighteen when he graduated with

distinction.

During his second year at the Dana Law School he was

mixed up in the attempted rescue of a fugitive slave named Anthony Burns.

During the fray an assistant of the U. S. Marshal was shot. Several persons

were arrested, among them Albert. Uncle

John went immediately to the jail to see Albert. He got word through to your grandmother in

Salem, "Sarah, I have seen the boy.

He is all right. Put on your

brightest bonnet and go to church, holding your head high." The complaint became one of riot and the

Grand Jury found no indictment.

After Law School he went to Europe and became a

student at Heidelberg, gaining the degree of Ph.D. In 1856 he began his law practice with John

A. Andrew at 19 Court Street, Boston.

Albert's interest had been Journalism as wall as law. He accompanied the expedition against the

Mormons under Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston in 1857, as correspondent of the New

York Tribune. Articles by him about this

and the ordeal of near starvation appeared in the "Atlantic Monthly"

in 1859 and are of great interest.

Finally in 1861 he became Governor Andrew's military secretary, the

office carrying with it the title of "Colonel", which he seldom used.

In 1874 he moved to New York to become managing editor

of the New York Evening Post. Then he

joined the editorial staff of the New York Herald, eventually becoming managing

editor of the Telegram. In the late

eighties — I don't know the year — Albert developed diabetes. He could not keep up the pace of work in New

York. Uncle Charles urged him to come to

Boston and help take care of his — Uncle Charles' — affairs. Mattie did not wish to leave New York, so

perhaps for a year or two Albert lived with his Uncle Charles and was busy in

some capacity with Cordley and Co. Finally Mattie

decided to move to Boston. They took a

house on Newbury Street where Albert died in June, 1891. His funeral was on the Saturday before our

wedding on June 30th.

Albert and Mattie had come to a large reception given

by Uncle Frank for me in February, 1891.

Albert was most cordial but Mattie refused to be introduced to me. This upset Sally and Mary Pickering who were

receiving with me and introducing me to the family friends. I could see that the incident annoyed Albert.

Uncle Charles died early in the nineties. He was always kind and pleasant. Mattie died about 1907, I think. The third of the Browne property which went

to Albert in 1885 went to Mattie's nieces.

After Albert's death Uncle Frank had been angry with Mattie for not

giving back some of the Browne things since there were no children by that

marriage. I remember that he spoke to me

about this. He said that ethically she

should have given them back to the Browne family.

This is a mere skeleton sketch of a very full,

interesting life. For anyone really

interested there is a good account of his life in the Sixtieth Anniversary

Report of the Harvard Class of 1853.

Looking at the portrait of the little seven-year old boy on your wall,

one could scarcely guess all the history and events and changes which would

come during his lifetime and in which he would have so large a share.

Louis Agassiz must have been

a remarkable man. Mr. Morse told me that

he was very interested in disseminating knowledge — a born teacher. Mr. Morse, of course, was one of his

scientific students. Mrs. Agassiz had a school in Cambridge to which Nellie was sent

and at which there were some interesting young women: Cousin Rebecca Browne

(Greene), Lucinda Howard who later opened the famous Howard School for Girls in

Springfield, Sally Howard, and several others.

Sally Howard married a Mr. Hayward and became the Bother of Mrs.

Andrews, whom you must remember in Cambridge, and of the lovely little dwarfed

Miss Hayward. Mrs. Andrews' daughter,

Betsy, has published some Howard and Hayward letters. Rebecca Bradford has

them. In them Nellie and Albert Browne

are mentioned. Sophie, Mrs. Hayward's

sister, was in love with Albert at one time, so the Haywards

told me. It was through the Howards that the friendship with the Welds started. Mr. Hayward was of Mayflower descent, and, my

goodness, it bristled out all over him.

Nellie lived with Mrs. Estes Howe. I am confused as to who she was. She was a person of a good deal of

personality. I used to think it was Mrs.

Samuel Gridley Howe, but now I do not think it was. It would be interesting to know what other Howes were in Cambridge at that time. I think Julia Ward Howe lived in South

Boston.

But to go back to Nellie. Cousin Rebecca

Greene used to say that Nellie was a lovely person, the loveliest girl in the

school. She may have been prejudiced, of course, but I think that it was

true. There was a splendid group of

young people in Cambridge and Boston then, just before the Civil War. Many of the young men never came back from

the war. When Robert Could Shaw's colored

regiment — the 54th — left Boston, it assembled on the Common. Luis Emillo, from

Salem, was commissioned captain that day and Nellie Browne pinned the captain's

bars upon his shoulders. He became the author of "The Brave Black

Regiment".

Perhaps you would like to be retold a few stories

which had to do with the Brownes. When the tunnel for the railroad was being

dug in Salem in 1836 or '37 Grandfather was going to his business on Derby

Street one day when he saw an overseer abusing a young Irishman who was digging

in the excavation. Grandfather interceded,

saying that if things did not improve for him to come to see him. This was very characteristic of him. The lad later did come and a good job on a

milk route was obtained for him. He was

a gifted person so Grandfather kept in touch with him and finally helped him to

buy a farm in Lancaster, N. H. Robert Jaques was his name.

Robert sent to Ireland for his brother, John, and soon they were

successfully raising horses and livestock.

It was at their farm that Grandfather used to visit and did much

tramping in the surrounding mountains.

At one time he was lost all night on the Stratford Peaks.

When your father and I were at Sugar Hill many years

later we learned that John's daughter was the telephone operator in Lancaster.

In 1906 a black sheep in the family tried to get your father to lend him some

money. Your father gave him ten dollars

which was never returned — a sad ending to the tale. Grandfather's old war horse, Maydoc, lived his last years at the Jaques'

farm. It was on one of his trips to

Lancaster that Grandfather came home without his shirts which Grandmother had

made for him.

I tell you this tale because it was a long one from

1837 to 1906.

You ask about the two silver spoons which were

evidently a premium or prize. Uncle Edward

Cox used to go to Illinois on business about hemp, whether growing it or buying

it, I do not know. He employed Abraham

Lincoln for one or two law cases. Grandfather visited Chicago and he and Uncle

Edward tried to persuade your great-grandfather Cox, unsuccessfully, to buy

some land there upon which later one of the important buildings of Chicago was

built. The silver spoons came from

Chicago and may have been a prize for Uncle Edward's hemp.

Speaking of hemp — in the forties Grandfather was

engaged by the government to investigate the possibilities of growing hemp in

this country, so he went to Kentucky to get in tough with Henry Clay about

it. The two men became friends. It was from "Ashlands"

in Lexington, Ky., Henry Clay's hose, that the ash logs, Henry Clay's gift,

were sent to Grandfather, probably most of the way by river and canal, and from

which the six not too beautiful ash chairs were made. Your Carey has two which should be labeled

some day because of the historical interest.

So far as I know, hemp has never been grown successfully in this land.

Here is a little story which I think you do not

know. Do you remember a portrait in the

Pickering house of a young girl — an early portrait? She was Alice Flint and was an ancestor of the

Brookses. She

came from North Andover. Her daughter

married a Browne, a son of Hannah Bartholomew and James Browne who went to live

near the Browne and Bartholomew Ponds — of course named for them. When she married, her mother gave her a

dowry. She liked pretty clothes and

dressed well. Church laws than limited

the amount of money which could be spent on oneself. Her clothes displeased the magistrates and

her case was brought before them. She pleaded her case well, — that she had

been given a dowry to do with as she liked and that she had a right to spend it

as she saw fit. I should say that she

was an early example of a feminist or "woman's rightser". She won her case, too.

Yes, I should love to tell you once more about your

father's portrait, for it has always seemed a lovely story to me.

Before Grandfather Browne went south, during the Civil

War, he commissioned an artist, as a surprise for his family, to paint a

portrait of your father, probably from a little photograph because he did not

remember sitting for it. Grandfather

bought an oval frame for it and put the frame away. When he came back the artist, Mr. Southard,

had died and his studio had been dismantled.

The portrait could not be traced.

So the frame remained in its green cover hanging in the storeroom, where

it remained for many years after I was married.

It may have been in 1904 or 1906, for at both those

times I was ill in bed, first, when Rebecca was born and, second, when I was

recovering from the long siege of peritonitis during which I nearly died. Hew clearly I can place certain events, — in

the hospital December, January and February, Aunt Margaret's marriage in March,

and Dr. Putnam's funeral in early April.

I went to it In Danvers in the electric car. How weak I was! I read headlines on people's newspapers on

the way about the San Francisco earthquake and fire.

Well, to go back, I was ill in bed when your father

came and stood at the foot of the bed and said, "The most astonishing

thing has happened. I have found my

portrait!" Whenever the storeroom

had been cleaned I had always wondered where the portrait of the little boy

was which should have been within that frame.

This news I could scarcely believe, for the portrait and frame had been

separate for over forty-five years. Your

father then told me that he had gone into Judge Holden's office and was led

into a back office where he had never been before. He was an alderman at the

time and he probably was there about city affairs. There on the wall was the portrait of himself. He exclaimed, "Judge Holden, where did you get

that portrait?"

The Judge replied, "I bought it when Southard's

studio was broken up and his pictures were being auctioned off. I took a fancy

to this one."

Your father then told Judge Holden the story of it and

asked if he could buy it. The Judge

wished to give it to your father but he insisted upon paying a small sum for

it. It is unfinished. Cousin Sarah

Smith, who was an artist, said not to touch it.

I have always loved it just as it is.

So the frame was brought downstairs, the portrait was

fitted into it, and the two parts, waiting so many years, were now a completed

whole.

Your father was very active in civic affairs. He was a member of the City Council and,

later, a member of the Board of Aldermen.

He was on the Water Commission or Board.

He was a very active trustee of the Salem Hospital for many years, until

the time of his death. He was a trustee

of Harmony Grove for a long time. At one

time ha was president of the Salem Fraternity, one of the first boys' clubs in

America; president of the Essex County Unitarian Association, having been its

treasurer earlier. He was on the standing committee of the North Church,

treasurer of that Society, and one of its four deacons. He was a member of the Civic Club and made a

study of all the shade trees in the city, their condition and their need. This was a splendid study, full of

information, which after his death someone borrowed and never returned to me.

I prize a letter Mr. Arthur West wrote to me after

your father's death, concerning his usefulness as a trustee of the hospital and

of his comradeship with the members of the board. He was a lovable man and I

have many happy memories of the years we spent together.